[Written March 2019]

Introduction

As our knowledge of climate change increases, we are seeing more alarming events surrounding the issue. These include the withdrawal by the Trump administration from the Paris agreement; the extreme weather events of 2018; the 2030 timeframe given by the Inter-Governmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) special report in 2018 and the protests of the yellow vest, extinction rebellion and school student strike movements. 2018 has seen a growing number of eminent academics speak critically of the IPCC reports due to their failure to include several factors regarding the positive feedbacks in the climate system that would accelerate climate change (CC). Some voices now even conclude that societal and environmental collapse is now unavoidable. In such a collapse, food becomes the primary concern of people and communities.

Calling Climate reporting, target setting and policymaking into question

An article published in 2018 titled ‘What Lies Beneath’ (WLB) (Spratt & Dunlop,2018) offers a stark review of the current paradigm in climate science research. Much of their critique is levelled at the IPCC which delivers predictions based on consensus building which are claimed to underpredict real outcomes (Spratt & Dunlop,2018). The WLB paper cites a long list of scholars and scientists that echo the same sentiment that the IPCC has underestimated the rate of CC progression (Spratt & Dunlop,2018). These individuals and groups are listed in table 1.

Table 1: A list of academics and institutions that endorse the case that reports are underestimating the rate of CC

| Sir Nicholas Stern, Kevin Trenberth, Professor Micheal E. Mann, Professor Kevin Anderson, Dr Barrie Pittock, Professor Ross Garnaut, Sydney climate council, Ian Dunlop, Professor Robert Socolow. |

| Other examples that claim that the IPCC underplays the situation (Xu, Ramanathan & Victor(2018); Wallace-Wells,(2018)). |

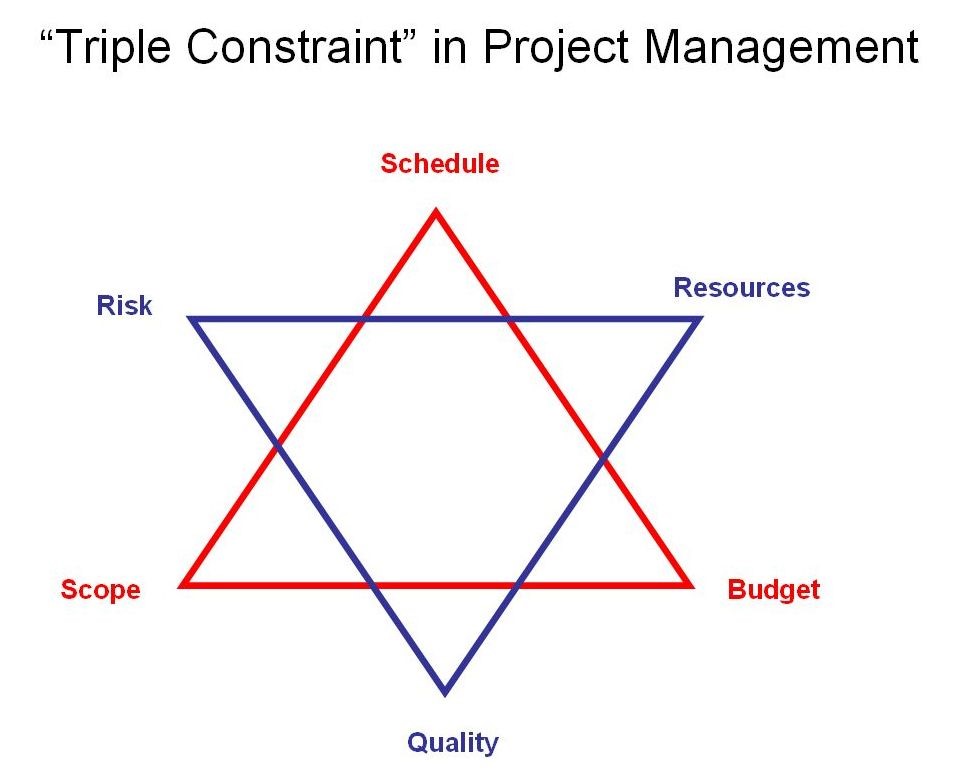

The message from these scientists is that our approach to predicting and modelling CC is inadequate to protect us from the worst outcomes. They call for a shift to an existential risk management framework that considers ‘the envelope of possibilities’ which include the worst-case scenarios (Spratt & Dunlop,2018). Existential risk is that which could lead to the extinction of humans. It requires full disclosure about the potential scope, risks and timeframes for global government to respond with effective action. This process is applied in the triple constraint model of project management as shown in figure 1. By considering an aggressive schedule in which CC may reach a threshold from where the stable environmental conditions become irrecoverable, we can then plan for the scope, risks, resources and budget to achieve the best quality of outcome. This threshold is widely discussed in the field to involve passing tipping points which can cause self-reinforcing feedback loops leading to ever increasing temperatures.

Figure 1: The triple constraint model as used in project management (source: Bogdan (2010))

A glaring omission of the IPCC reports are contributions that relate to these feedback processes (USGCRP,2017) which can cause abrupt and potentially irreversible changes. They justify this by stating that the information about such tipping points that cause feedback mechanisms and the ways in which they interact is still limited (Rocha et al,2018). Examples of the feedbacks not considered are shown in table 2.

Table 2: Examples of the feedback mechanisms not considered by most climate models and the IPCC predictions.

| Thawing permafrost: Permafrost regions of the Arctic, when thawed due to increased temperatures, release the potent greenhouse gas (GHG) methane from existing stores and rotting biomass. An abrupt permafrost carbon feedback from the thaw beneath thermokarst lakes are projected to double radiative forcing from the predicted gradual thaw rate within this century (Anthony et al,2018). This warming will cause further permafrost melt and release of methane. |

| Methane hydrates: Methane, when frozen in water, forms a hydrate ice water. Frozen into the seabed is a reservoir of such methane hydrates (Archer,2007). If this were to melt it would release the methane and cause further warming thereby forming a feedback mechanism causing ice to melt at further depth in the seabed. |

| Polar ice melt: Melting sea and land ice at the poles reveals the seawater or land beneath it which decreases the albedo for incident radiation and more is absorbed by the planet than would be reflected by ice. This further warms the land, atmosphere and oceans causing further melting (Andry, Bintanja & Hazeleger,2017). |

| Increased water vapour in the air: Global warming can cause more sea and land water evaporation which creates more clouds. This traps more heat in the atmosphere and exacerbates the greenhouse effect (Trenberth et al,2015). |

| Migration of tropical clouds: Movement of clouds away from tropical regions toward the poles can lead to decreased rainfall and expansion of sub-tropical zones (Norris et al,2016). New research suggests that clouds could disappear completely at an atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration of 1200 ppm. The planet could be on track to reach this by 2100 in a ‘business as usual’ scenario. This would happen in a world which is 4°C warmer than pre-industrial levels (PIL) and would further warm the world another 8 ° C. Such an event would wipe out most life on earth including humans (Schneider, Kaul & Pressel,2019). |

| Green carbon sinks – forests, terrestrial plants and soils |

| Forests and plants: With increased deforestation and forest dieback we see less CO2 absorbed by photosynthetic plants and trees. This allows atmospheric CO2 to rise which increases temperatures further and causes more forest dieback. Forest dieback contributes to precipitation reduction, firstly, by the biophysical feedback of reduced forest cover reducing evaporative water recycling. Secondly through the biogeochemical feedback by the release of CO2 adding to global warming. There is also a physiological forcing whereby rising CO2 forces stomatal closure which is the site of the plant through which gaseous exchange occurs (Betts et al,2004). Forests and terrestrial plants absorb carbon through a phytolithic sequestration process which is coupled to the biogeochemical silicon cycle. Silicon fertilizers can enhance carbon uptake (Song et al,2017). |

| Soils: Soils contain more carbon stores than all terrestrial vegetation and the atmosphere combined (Batjes,2016). Intensive agriculture from overgrazing and tilling contributes to depleting this vital carbon sink which could be managed better with regenerative agriculture methods (Marshall,2015). |

| Blue carbon sinks – Oceans and coastal ecosystems |

| Oceans: The solubility pump describes the process of atmospheric CO2 dissolving in seawater and it is the primary mechanism of CO2 uptake in ocean waters (Lade et al,2018). The solubility of CO2 in seawater decreases with increasing water temperature and thus with less CO2 absorbed there is increased heating which further reduces seawater CO2 solubility. The biological pump is that which describes the ocean life which sequesters carbon through the food web. An essential part played in this food web is that of phytoplankton which absorbs carbon into their shells. Ocean acidification, which increases with the increased amount of CO2 absorbed, reduces the ability of phytoplankton to thrive and form the carbonates needed for their shells thus reducing their numbers and sequestration capacity. |

| Coastal ecosystems: Mangrove forests along the coasts are also a carbon sink which if lost to sea level rise would reduce CO2 absorption and create a feedback loop (Wilson,2017). |

| Teal Carbon sinks – Freshwater wetlands |

| Wetlands: Wetlands hold a disproportionately large amount of carbon when compared to other soils. They only account for 5-8% of the earth’s land surface yet hold between 20-30% of total soil carbon (Nahlik & Fennessy,2016). |

| Other colour-coded carbon types are black and brown carbon. Black carbon comes from particles like soot which are left over from incomplete combustion of fossil fuels. These can be carried in the air and deposit on snow and ice which reduces the albedo effect and causes more heat to be absorbed rather than reflected. Brown carbon is the name given to GHG’s such as CO2 and methane. |

Reassessing the credibility of the IPCC models

The IPCC analyses not only exclude a large range of potential accelerants to CC but their consensus building is compiled using research that is out of date by the time they publish. They only include research that is completed at least 3 years prior to the release of the report (Barras,2007). Since international policy-making uses the IPCC reports as their sole reference point for target setting (Spratt & Dunlop,2018) it is unlikely that such targets will be ambitious enough to tackle the problem. Indeed, the voluntary emission reductions set at Paris have been projected to lead to at least a 3.4 °C temperature increase above PIL by 2100 if fully implemented (CAT,2017).

The WLB paper emphasizes the urgency of altering our assessment process of the risks involved to inform the actions we take. An existential risk management-framework is proposed as an improvement to the current consensus-building method the IPCC uses which is based on temperature thresholds. Then to properly address CC we must act and respond as though this is the emergency that it really is (Spratt & Dunlop,2018).

Civilization collapse and environmental breakdown

In the paper titled ‘This is a crisis’, it is concluded that we have now entered environmental breakdown which puts into question the viability of future human society (Laybourn-Langton, Rankin & Baxter,2019). Some implications of environmental breakdown mentioned include malnutrition of displaced people; threats to the infrastructure of property, energy systems, transport and communication networks; starvation and ill health from decreased crop yields and food shocks creating a strain on food supply chains. This type of environmental breakdown acts as a ‘threat multiplier’ which in the extreme case could lead to a ‘runaway collapse’ of economic, social and political sectors of society which spread through the globally interconnected systems (Laybourn-Langton, Rankin & Baxter,2019).

This type of societal and environmental collapse has now been considered by some to be an inevitable outcome of the crisis we are now facing (Bendell,2018; Read,2018; Servigne & Stevens,2015). There is even a whole field devoted to the study of collapse called collapsology. There are a few interpretations of civilization collapse being communicated. Some take the view that we are to grieve and accept this loss to help motivate action (Bendell,2018; Servigne & Stevens,2015; XR,2018). In table 3 we theorise that society has been going through this grief process by attributing certain academic, public and governmental actions to the 7 stages of grief (the modified version of Kubler Ross model).

Table 3: The seven stages of grief humanity has displayed in reaction to the existential threat of climate change

| Shock: On a societal and personal level our reaction to the discovery of the threats of climate change is strong. We are shocked that the consequences could be so severe that it poses an existential threat to us that we struggle to comprehend this reality. |

| Denial: Outright climate denialism has peppered the conversation by some academics and corporate affiliates. The lack of action demonstrates a level of denial despite the decades of governmental negotiations on CC. Public ignorance of the full implications of CC is commonplace. People would rather maintain ignorance than confront the realities of dealing with CC. For those with wealth and power, it is an inconvenience to them and it appears it is preferred to pacify the public by vaguely acknowledging it and sidestep the harsh realities. |

| Anger: There have been countless protests and movements attempting to invigorate action on climate change but none have captured the attention of the public like what has been seen in 2018 and early 2019. The yellow vest protests, whilst not explicitly protesting for environmental concern, have been motivated in response to a fuel tax which was created to help cut GHG emissions. The extinction rebellion movement has engaged in civil disobedience to rebel against the inaction as we march towards extinction of the human race. The school youth strikes have increased attention on the issue and voices of the disillusioned youth are being heard. |

| Bargaining: The current and previous proposals to tackle the issue have been not nearly enough to halt CC. The ideas of sustainability, mitigation, transformation and adaptation have fallen on deaf ears and most of the solutions do not tackle the largest, most difficult issues such as planetary overpopulation. There has been an avoidance of facing the toughest transformational policies and instead, we have placed our hope in adding complexity to the existing system without needing to change the status quo. The ideas of geoengineering, cloud seeding, CO2 sequestration and carbon extraction technologies are a last resort and defence, but none of these ideas has been tested at scale and relying on them is setting ourselves up to fail. |

| Depression: The feelings of hopelessness and apathy by those who have looked closely at the complexity of this issue shows in the lack of commitment to any concrete plans to overhaul the system. It is clear that we would need to change everything but keeping everyone happy and the changes be ethical, never mind getting the political will to introduce such changes, seems an impossible task. With the Trump administration withdrawing from the Paris agreement this seems more an act of giving up rather than denial. The solutions would require a disentangling of all of our highly interconnected, complex systems at the cost of convenience and excess for many. The loss of this lifestyle seems too depressing and unacceptable to many. |

| Testing: This is the critical evaluation of the worst-case scenario threats from CC with an honest and assertive appraisal of the dangers communicated to the public, scholars and government. We are seeing this now with the case being made that the IPCC reports are too conservative to be relied upon to set targets. With the real threat of collapse being discussed openly and the call for a need for deep adaptation to avert the worst possible outcomes. |

| Acceptance: This stage is one of accepting that a collapse of civilization and environment are a very likely scenario and of finding a meaningful way forward. This stage is about safeguarding what is most important upon facing the reality of loss. This type of safeguarding is like that of the decision made by the British government in world war 2 to send children that lived in cities to the rural towns and villages to protect them from the bombing. Another example is the decision made by the captain of the Titanic to send children and females first to the lifeboats as the ship began to sink. For humanity, safeguarding might be to ensure the ability of a number of humans to survive as long as possible and avoid or at least delay a human extinction. It would include taking precautions to fortify the environment’s ability to recover in a potential post collapse rehabilitation phase. We may be at this stage of grief now, but also maintaining hope that our other and as yet formulated strategies to combat climate change will work. The old adage hope for the best, prepare for the worst certainly applies to climate change. |

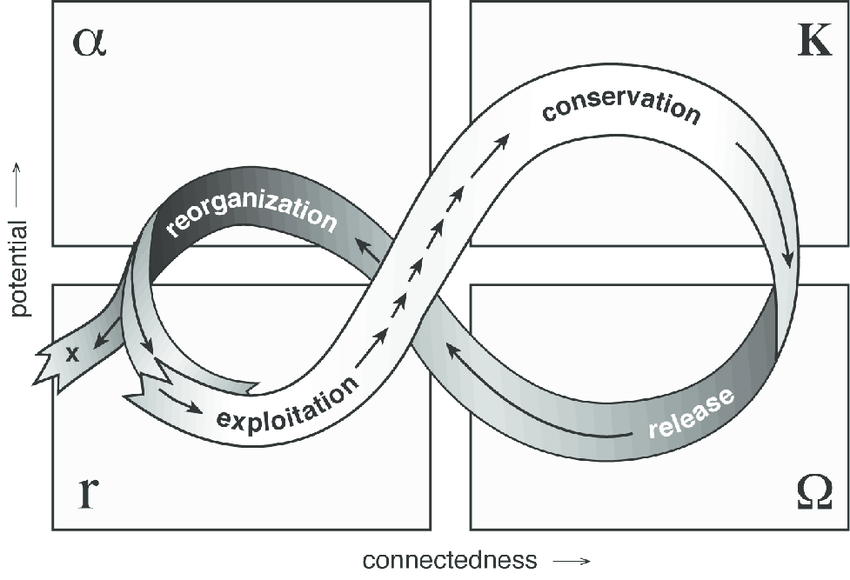

Other viewpoints on the effects of a collapse take the contrary opinion that we are not to grieve the loss of civilization but welcome it as the true remedy for the environment (Casaux,2018). A more balanced view between grieving and welcoming collapse is given in a paper which describes it as an opportunity for a successor civilization to emerge (Read,2018). This decay and potential rebirth of civilization have been described as inhabiting the ‘back loop’ or reorganization phase of the resilience adaptive cycle (Wakefield,2017) as shown in figure 2. These phases of the adaptive cycle are described in table 4.

Figure 2: The resilience adaptive cycle (Source: Gunderson & Holling,2002)

Table 4: Descriptions of the phases of the resilience adaptive cycle (adapted from Gunderson & Holling,2002)

| Exploitation/growth: |

| Fast accumulation of resources |

| Competition and seizing of opportunities for resources |

| Increasing complexity, connections and diversity |

| High but decreasing resilience |

| Conservation: |

| Slowed growth |

| Resources are stored and used to maintain the system |

| Stable with high certainty but reduced flexibility and resilience |

| Collapse/Release: |

| Chaotic collapse and release of capital |

| High uncertainty and resilience low but increasing |

| (Re)organization: |

| Innovation and resilience are high |

| Restructuring and adapting to new conditions |

| The greatest uncertainty in the cycle but with high resilience |

Building upon our current strategies of response to climate change

The strategies developed to combat climate change fall into several broad categories but until recently none have gone far enough to imagine a response to the collapse of society or the environment. Such a strategy called the deep adaptation agenda has now been explored in a recent paper (Bendell,2018). To add to this collection of strategies we propose a subcategory of deep adaptation as a safeguarding strategy. This acts to secure a larger subset of the population than currently existing, with a food self-sufficient, off-grid living infrastructure to survive and live through a collapse. It also emphasizes regenerating our natural carbon sink environments which might not only mitigate CC before a collapse but could deliver the fastest recovery of the climate post-civilization collapse, if this is at all possible. The range of strategies considered by the field so far is briefly overviewed in table 5 with the addition of the safeguarding strategy. The ideas of deep adaptation and safeguarding are most applicable to the ‘back loop’ reorganization phase of the resilience adaptive cycle of figure 2 and table 4.

Table 5: Proposed strategies to combat or prepare for climate change

| Sustainability: Using methods to limit GHG emissions to slow and reverse climate change progression This range of strategies is described by (Ripple et al,2017) Prioritise creating connected, well-funded and managed reserves for terrestrial, marine and aerial habitats Maintain ecosystems by halting the conversion of forests, grasslands and other native habitats Reforestation Rewilding, restore apex predators Prevent defaunation, poaching crisis Reduce food waste with better education and infrastructure Eating fewer animal products Promote female education and family planning to decrease birth rates Outdoor nature education for children Divesting to encourage environmental positive change Expand green technologies and renewable energy Phase out subsidies for fossil fuels Revise economy to take account of real costs to the environment including pricing, taxation and incentives which will help reduce wealth inequality Estimating a scientifically defensible, sustainable human population size for the long term while rallying nations and leaders to support that vital goal Reduce intensive agriculture and move to agroecology and permaculture methods of farming |

| Mitigation: Limit the magnitude or rate of CC, to reduce the loss of life or damage by lessening the impact of adverse events. Collective actions for the public good. Prepare coastal and urban flood defences against sea level rise and extreme rainfall events respectively Form emergency response plans for extreme weather events such as wildfires, flooding and droughts Increase energy efficiency such as improving building insulation Phase out fossil fuels and switch to low carbon sources Removal of CO2 from the atmosphere Having fewer children Live car-free Eating a plant-based diet Reforestation and afforestation Switch to regenerative agriculture methods Carbon emissions trading, GHG emissions tax, Carbon offsetting |

| Adaptation: Incremental changes to civilization to avoid the worst effects of climate change. Diversifying energy sources and innovating new technology Intensifying green energy usage Revitalizing old methods such as in crop agriculture, eg. biodynamic, organic Change mobility habits using more public transport and car sharing Rationing fuel or animal products |

| Transformational adaptation: Non-incremental changes to civilization to avoid the worst effects of climate change System-wide change or changes across more than one system Focus on future and long-term change Direct questioning of the effectiveness of existing systems, social injustices and power imbalances |

| Resilience: The ability to prepare for, absorb, recover from and more successfully adapt to adverse events This list is described by (Partidarlo,2011) To assume a socio-ecological understanding system thinking to understand the structure and dynamics of the system Recognize uncertainties, disturbances and thresholds in the context of complexity Use the adaptive cycle model to understand system trajectories Consider cross-scale interactions and interdependencies Increase the adaptive capacity of and to transform the system when crucial Scan for vulnerabilities to avoid collapse and maintain resilience Shift the mindset from command and control to learn and adapt |

| Deep adaptation: Reduce the harm of a potential collapse by securing essential systems Proposed by (Bendell,2018) Building water and communication systems that won’t fail if the power grid collapses Protecting pollinating insects Pull back from the coast Close climate exposed industrial facilities such as nuclear power stations Planning for food rationing Let landscapes return to a natural state Give up expectations for certain types of consumption Rely more on the people around us |

| Safeguarding: The process of creating a safety net for humanity and the environment to provide the best hope of avoiding human extinction and climate recovery. Attempting to ensure permanence and perpetuation of humanity. Recommendations by the author: Raise the alarm among academics about the now highly likely possibility of environmental and societal collapse. Open a dialogue to form a consensus position ready to inform governments and wealthy private groups to take action in the form of safeguarding. Planning for the preservation of the human species by setting an estimated desirable minimum number of humans to recolonize the planet post societal collapse and acting to save that number of healthy, fit people. Create purpose-built, self-sufficient, off-grid communities in regions considered to be least or last effected by CC Adapting small settlements such as rural villages to be ready for or transformed into off-grid living communities that are self-sufficient Prepare the planet to naturally absorb as much CO2 as possible which may mitigate CC but also hasten a potential reversal of climate conditions post societal collapse Reforestation, afforestation, planting of mangrove forests and seagrass and kelp forests Locate some of these off-grid safe havens in areas where this greening exercise by these groups can continue during and after a societal collapse |

By prioritizing the safeguarding strategy now, there are effects of these actions which can create ripple effects in society. By setting a desirable minimum number of humans to secure, this creates an achievable goal which would be seen in society as an effort to avoid the very worst-case scenario which is human extinction. By reducing the probability of this occurring it can provide people with the hope that humanity has taken steps to secure itself as best it can. This could spur more to want to survive and those with the private resources to do so may flock to rural villages and create or join an effort to transform them into off-grid-ready communities. It might shift this apathy related inaction of humanity stemming from the perception that it is unable to do anything to fight climate change at a scale which will be lasting. The fortification of natural systems which act as carbon sinks is the most economic use of our energy since the initial investment requires very little materials or maintenance and it has the potential for the biggest payoff in the long run.

Timeframes for collapse

The warmest five years on record have occurred in the last five years and the warmest 20 over the last 22 (WMO,2019). With the 2018-19 summer in Australia being the warmest ever recorded (AGBM,2019) and anomalous warmth in Europe with the warmest February day ever recorded in the UK (MET,2019a), we can see the effects of climate change are being felt globally. The MET office predicts we may see a temporary global temperature surge past the 1.5 °C above PIL in the next 5 years (MET,2019b) which is viewed as a critical temperature rise to not surpass to avoid the worst climate scenarios. This does suggest we are seeing an accelerated progression towards a 1.5°C rise above PIL than the IPCC special report forecasts to be around 2030 (IPCC SR15,2018).

Other factors aside from feedback mechanisms which are not considered by the IPCC report include solar weather. Solar weather plays a role in global temperatures (SNSF,2017) as it moves through an 11-year cycle from maximum to minimum of solar activity. We are currently at solar minimum with no sunspots recorded at all during February 2019 (spaceweather.com,2019). There are suggestions we may be heading into a Grand Solar Minimum where sunspot numbers drop dramatically for decades at a time and this has correlated with markedly lower temperatures (Zachilas & Gkana,2015). Solar activity has been weakening over the past several solar cycles and if such a Grand Solar minimum does occur this could somewhat counteract global warming thus offering us a longer period to adapt to it.

The greatest solar activity occurs over the 5 or so years which span the midpoints between maxima and minima centred around the maximum. The predicted forthcoming period will be approximately between 2022 and 2028 with maxima peaking around 2024 (Odenwald,2017). If this maximum is coupled with the emergence of one or more El Nino conditions during that period, we might expect temperatures to accelerate higher faster than predicted for that time. This could impact potential feedback loops and push them passed tipping points sooner if they had not reached this threshold already. With the IPCC providing a timeframe up to 2030 beyond which the effects of CC will be much more pronounced it might be more accurate to shift this timeframe closer to 2025. With the evidence cited here, it would be prudent to take swift action to safeguard humanity, mitigate the effects of and adapt to CC.

The precautionary principle has not yet been invoked effectively by policymakers, which when applied, answers the call of social responsibility to protect the public from harm when scientific investigation has found a plausible risk (Read,2017). The task of ensuring safety from CC for a global population nearing 8 billion is one of staggering magnitude due to the complexity of our systems. Yet it is not too late to at the very least use the precautionary principle to build infrastructure to sustain a relatively small population that will be more protected from collapse. The limited window of opportunity suggested here places safeguarding as the most realistically attainable goal in such a short amount of time when compared to all our current proposed strategies to deal with CC.

Food in a world after civilization collapse

In a post-collapse world, the services and goods in the developed world would be unlikely to be provided. Cities would be most affected which rely on continuous delivery of food from farms outside the city and imported from all around the world. Developed countries also no longer keep vast surpluses and stockpiles of food as they operate on a ‘just in time’ delivery system which ships in food to be replaced as it is purchased. It is possible that the electrical grid and even water supply would eventually falter and cease to function without the engineers and personnel available to maintain and run these systems.

It is considered here that rural, off-grid living provides the best chance to survive this post-collapse society. There are many variations of this lifestyle from around the world which persist today. Their primary activities are to farm and grow food and it is often done in a collective community manner. A good example is in China which is the most populous country in the world and where approximately 42% live in rural regions (World Bank,2018). Full electrification of the country was only completed in 2015 which is a few decades behind many other industrialized nations (Gang,2017). Because of this, many rural communities still use traditional, non-electric methods of growing, harvesting, cooking and storing food.

There are many other similar examples of such agriculture and living methods which include the Amish and Mennonites, the Israeli Kibbutz, Traditional rural communities, Intentional communities, Collective farming, Civic agriculture, Homesteading and Tropical fruit orchard ownership. Some details of these styles of self-sufficient and in some cases off-grid living are given in table 6.

Table 6: Examples of food self-sufficient lifestyles from around the world

| Amish and Mennonite: These religious people shun most electrically powered devices and other modern conveniences and pride themselves on working hard. Items generally disallowed from use include cars, tractors, propane gas, refrigerators and inside flush toilets. Many do allow the use of motorized washing machines though. Some Mennonite orders allow the use of cars, electricity, phones and computers. They farm their own foods and can and pickle produce as a way of preserving the harvest. |

| Kibbutz: A kibbutz is generally based on a collective community ideal which focuses mainly on agriculture. A hard work ethic in cultivating the land is the main feature which also makes them food self-sufficient. They most often subscribe to an ideology of equality which was originally in the form of socialism. |

| Traditional rural communities: Many rural communities around the world still operate without a connection to the electrical grid and some that have electricity still use the traditional tools and methods of food production, cooking and storing. Using firewood to cook on stoves, in ovens or over open fires is essential to their lifestyle. Home preservation with oils, alcohols and fermentation is used to extend the lifetime of the harvest. |

| Intentional community: Typical values of such groups include self-sufficiency, simplicity and minimalism, sustainability and communal living. |

| Collective farming: The agricultural work is run by multiple farmers who work together to cultivate and farm the land. Collectivization is the process of joining separate farmlands under one joint enterprise. |

| Civic agriculture: Agriculture is viewed as the responsibility of an entire community and it connects the farmer to the community through a social connection. The sustainability of this type of rural agriculture is a central value which aims to create a self-sustainable local economy. |

| Homesteading: The lifestyle is one of subsistence farming and self-sufficiency but is different from communal types of living as it is more of an individual or family approach. It involves home preservation of foods such as canning, pickling, drying and traditional forms of storing produce. Modern homesteading often uses renewable technology to power their homes with solar and wind power. |

| Tropical fruit orchard ownership: Tropical fruit orchards provide an ideal form of subsistence farming as fresh, high nutrient fruits are optimal for our health. It is possible to thrive on a largely raw, plant-based diet with a high fruit sugar content. Limited by their geographical location requiring at least sub-tropical warmth and fertile soils to grow in, they are only viable closer to equatorial regions. |

Conclusions:

This case study conforms to the triple constraint model of project management in the case of climate change which threatens to collapse environmental and societal systems. The imperative of such a project is to avert human extinction and preserve the habitability of the planet. We have determined that the scope for this project thus far has been inadequate to assess the magnitude of the problem as shown by the incomplete IPCC reporting methods. They ignore the risks of feedback loops in their predictions and now it is believed by some that we risk environmental and societal collapse. The schedule for these events is given as a rough approximation to happen nearer to 2025 than 2030 contrary to the IPCC special report prediction. The resources to combat the issue are the strategies humanity has devised thus far which are extended to include the newly formed deep adaptation agenda and the author’s suggestion of a safeguarding component. The budget for this action is the will of individuals to act including political and powerful individuals. Highlighting the grieving process as stages of the collective human response to this crisis shows we appear to be reaching an acceptance of the loss of industrialized civilization. When applied to food, the quality of the outcome is determined by the previous factors. It is concluded that self-sufficient, off-grid and traditional means of food production, cooking and storing is the best and safest way to ensure the survival of the largest number of individuals in the case of collapse.

References:

Andry, O. Bintanja, R. Hazeleger, W. (2017) Time dependent variations in the arctic surface albedo feedback and the link to seasonality in ice. Journal of climate 30(1) 393-410

Anthony, K.W. Deimling, T.S. Nitze, I. Frolking, S. Emond, A. Daanen, R. Anthony, P. Lindgren, P. Jones, B. Grosse, G. (2018) 21st-century modelled permafrost carbon emissions accelerated by abrupt thaw beneath lakes. Nature Communications. 9(3262)

Archer, D. (2007) Methane hydrate stability and anthropogenic climate change. Biogeosciences 4 521-544

Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology (AGBM) (2019) Australia in summer 2018-19. Available at: http://www.bom.gov.au/climate/current/season/aus/summary.shtml

Barras, C. (2007) Rocketing CO2 prompts criticisms of IPCC, New Scientist, 24 October 2007

Batjes, N.H. (2016) Harmonized soil property values for broad scale modelling (WISE30Sec) with estimates of global soil carbon stocks. Geoderma 269 61-68

Bendell, J. (2018) Deep adaptation: A map for navigating climate tragedy. IFLAS occasional paper 2. Institute for leadership and sustainability. Available at: http://www.lifeworth.com/deepadaptation.pdf

Betts, R. Cox, P. Collins, M. Harris, P.P. Huntingford, C. Jones, C.D. (2004) The role of ecosystem-atmosphere interactions in simulated Amazonian precipitation decrease and forest dieback under global climate warming. Theoretical and applied climatology. 78(1-3) 157-175

Bogdan, C. (2010) “Triple constraint” in project management, available at: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/file:Tripleconstraint.jpg

Casaux, N (2018) The problem of collapsology. http://partage-le.com/2018/01/8648/

Climate Action Tracker (CAT) 2017, ‘Improvement in warming outlook as India and China move ahead, but Paris Agreement gap still looms large”, 13 November 2017, http://climateactiontracker.org/publications/briefing/288/Improvement-in-warming-outlook-as-India-and-China-move-ahead-but-Paris-Agreement-gap-still-looms-large.htm

Extinction Rebellion, (2018) https://rebellion.earth/who-we-are/

Gang, H. (2017) Three lessons from China’s effort to bring electricity to 1.4 billion people. Available at: https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/9934-Three-lessons-from-China-s-effort-to-bring-electricity-to-1-4-billion-people

Gunderson, L. Holling, C.S. (2002) Panarchy: Understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Washington DC: Island Press

IPCC SR15 (2018), Global warming of 1.5°C, IPCC

Lade, S.J. Donges, J.F. Fetzer, I. Anderies, J. M. Beer, C. Correll, S.E. Gasser, T. Norberg, J. Richardson, K. Rockstrom, J. Steffen, W. (2018) Analytically tractable climate-carbon cycle feedbacks under 21st century anthropogenic forcing. Earth.syst.Dynam. 9 507-523

Laybourn-Langton, L. Rankin, L. Baxter, D. (2019) This is a crisis. Facing up to the age of environmental breakdown. IPPR. Available at: https://www.ippr.org/research/publications/age-of-environmental-breakdown

Marshall, L. (2015) Organic-plus? Natural foods merchandiser; Badle 36(10) 23-24, 26

Met Office UK (2019a) Record breaking February, mild winter. Available at: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/about-us/press-office/news/weather-and-climate/2019/february-and-winter-statistics

Met Office UK (2019b) Decadal forecast. Available at: https://www.metoffice.gov.uk/research/climate/seasonal-to-decadal/long-range/decadal-fc

Nahlik, A.M. Fennessy, M.S. (2016) Carbon storage in US wetlands. Nature Communications 7: 13835

Norris, J.R. Allen, R.J. Evan, A.T. Zelinka, M.D. O’Dell, C.W. Klein, S.A. (2016) Evidence for climate change in the satellite cloud record. Nature 536 372-375

Odenwald, S. (2017) Waiting for the next sunspot cycle: 2019-2030. HuffingtonPost. Available at: https://www.huffingtonpost.com/dr-sten-odenwald/waiting-for-the-next-suns_b_11812282.html

Partidarlo,M.R. (2011) SPARK: Strategic planning approach for resilience keeping. European planning studies 19(8) 1517-1536

Read, R. O’riordan, T. (2017) The precautionary principle under fire. Environment science and policy for sustainable development. 59(5) 4-15

Read, R. (2018) This civilization is finished: So what is to be done? IFLAS occasional paper 3. Institute for leadership and sustainability. Available at: http://lifeworth.com/IFLAS_OP_3_rr_whatistobedone.pdf

Rocha, T.C. Peterson, G.Bodin, O. Levin, S. (2018) Cascading regime shifts within and across scales. Science 362(6421) DOI: 10.1126/science.aat7850

Schneider, T. Kaul, M. Pressel, K.G (2019) Possible climate transitions from breakup of stratocumulus decks under greenhouse warming. Nature geoscience 12 164-168

Servigne, P. Stevens, R. (2015) How everything can collapse: small manual of collapsology for the use of the present generations. Ed. Du Seuil

Spaceweather.com (2019) A month without sunspots. Available at: http://www.spaceweather.com/archive.php?view=1&day=01&month=03&year=2019

Spratt, D. Dunlop, I. (2018) What Lies Beneath. The understatement of existential climate risk. Breakthrough. National centre for climate restoration. Available at: https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/148cb0_a0d7c18a1bf64e698a9c8c8f18a42889.pdf

Song, Z. Liu, H. Stromberg, C.A.E. Yang, X. Zhang, X. (2017) Phytolith carbon sequestration in global terrestrial biomes. Science of the total environment 603-604: 502-509

Swiss National Science Foundation (SNSF) (2017) Reported by: https://phys.org/news/2017-03-sun-impact-climate-quantified.html

Trenberth, K. E., Y. Zhang, J. T. Fasullo, and S. Taguchi (2015), Climate variability and relationships between top‐of‐atmosphere radiation and temperatures on Earth. J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 120(9) 3642-3659

USGCRP (2017) Climate Science Special Report: Fourth National Climate Assessment, Volume I, US Global Change Research Program, Washington, DC, USA.

Wallace-Wells, D. (2018) UN says that climate genocide is coming. But it’s worse than that. NYmag, Intelligencer. Available at: http://nymag.com/intelligencer/2018/10/un-says-climate-genocide-coming-but-its-worse-than-that.html

Wakefield, S. (2017) Inhabiting the Anthropocene back loop. Resilience. 6(2) 77-94

William J. Ripple, Christopher Wolf, Thomas M. Newsome, Mauro Galetti, Mohammed Alamgir, Eileen Crist, Mahmoud I. Mahmoud, William F. Laurance, 15,364 scientist signatories from 184 countries; (2017) World Scientists’ Warning to Humanity: A Second Notice, BioScience, 67(12) 1 1026–1028, https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/bix125

Wilson, R. (2017) Impacts of climate change on mangrove ecosystems in the coastal and marine environments of Caribbean small island developing states (SIDS). Caribbean marine climate change report card; science review: Science Review 2017 60-82

World Bank (2018) Rural population (% of total population). Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/sp.rur.totl.zs?year_high_desc=true

World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) (2019) The state of the global climate in 2018. Available at: https://public.wmo.int/en/media/press-release/wmo-confirms-past-4-years-were-warmest-record

Xu, Y. Ramanathan, V. Victor, D.G. (2018) Global warming will happen faster than we think. Nature. 564. 30-31

Zachilas, L. Gkana, A. (2015) On the verge of a grand solar minimum. A second Maunder minimum? Solar Physics. 290(5) 1457-1477