[Essay written February 2020]

Introduction:

Our species is now in severe danger from the threat of climate change. This requires us to invoke the precautionary principle which is described as answering the call of social responsibility to protect the public from harm when scientific investigation has found a plausible risk (Read,2017). Recent data analyses show that 2019 had the warmest ever global ocean temperatures (Cheng et al. 2020); the second warmest annual land temperatures (NOAA,2020); the second largest summer arctic ice melt (NSIDC,2020) and the highest carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere (NOAA,ESRL,2020), all since records began. The IPCC 1.5 special report states that greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions must fall by 45% by 2030 and by 80% by 2050 (IPCC SR15,2018). The problem with the IPCC predictions is that they fail to include most positive feedback mechanisms of nature’s globally interconnected systems (Spratt & Dunlop,2018). This gives us reason to believe we must act much faster than previously anticipated and with much more drastic actions.

Climate change is dependent on multiple factors of which the most impactful include GHG concentrations in the atmosphere. Using a systems-based approach the variables of global civilization are listed and organised in a geometric and tabular model titled the Planetarian framework developed by the author of this policy brief (Goldson, 2020). This divides the system of Earth’s civilization into three units of the system rules, input and output with subunits describing multiple subsystems as shown in table 1. Subunits I and K refer to human designed civilization which is split into broad categories as shown in tables 2 and 3 respectively.

TABLE 1: The units, subunits and adjuncts of the Planetarian framework

| Unit | Subunit designation | Geometric representation | Subunit of framework described | System Units and Adjuncts description |

| Primary = POWER | 00 | Centroid | The laws of Physics | System Rules |

| Primary | X | Sphere X | Variables which determine the state that two or more people or groups will exist in between each other. | System Rules |

| Primary | Y | Cube 1 | The general states that individuals, groups, tribes, nations and alliances can be in regard to the other. | System Rules |

| Primary | Z | Sphere 0 | The DNA and neurodevelopment which determines neurochemistry | System Rules |

| Primary | Ω | Dodecahedron 1 | The general rules of neurochemistry that determine decisions, actions and behaviour of individuals | System Rules |

| Primary | Φ | Sphere 1 | The meaning of life | System Rules |

| Primary | A | Icosahedron 1 | The rules of power | System Rules |

| Primary | B | Sphere 2 | Human philosophy | System Rules |

| Primary | C | Octahedron 1 | Fundamental Human and Natural systems | System Rules |

| Secondary = THE HUMAN CONDITION | D | Sphere 3 | Human rights and Human nature | System Input – Self interaction |

| Secondary | E | Stellated Octahedron (merkaba) | The human condition – Interrelational tendencies | System Input – Self interaction |

| Secondary | F | Sphere 4 | Human beings and Personal actions | System Input – Individual humans |

| Secondary | G | Cube 2 | The human experience and lifecycles | System Input – Individual humans |

| Tertiary = PLANETARY BOUNDARIES | H | Sphere 5 | Rules for Civilization design and structure | System Output |

| Tertiary | I | Dodecahedron 2 | Human designed Civilization infrastructure – Human mental constructs | System Output |

| Tertiary | J | Sphere 6 | Information used to determine international agreements on action, resource use and allocation | System Output |

| Tertiary | K | Icosahedron 2 | Human and environmental physical systems | System Output |

| Tertiary | L | Sphere 7 | The human capacity to overcome challenges and innovate The Planetarian Hive Mind The collective willpower, intelligence, psychological capacity and capability to extend the longevity of the existence of the human species in the face of existential threat from climate change. | System Output |

| Tertiary | M | Octahedron 2 | Earth’s primary systems for human survival | System Output |

| Tertiary | N | Sphere 8 | Variables which contribute to the overall radiative forcing amount on earth | System Output |

| Tertiary | O | Cube 3 | Radiative Forcing Factors on Earth | System Output |

| Tertiary | P | Sphere 9 | Variables which can increase or reduce potential positive feedback loops in environmental systems | System Output |

| Tertiary | Q | Dodecahedron 3 | Positive Feedback loops in Earth’s environmental systems | System Output |

| Tertiary | R | Sphere 10 | Variables which effect and determine the limits that Earth’s natural systems can reach and maintain a dynamic equilibrium | System Output |

| Tertiary | S | Icosahedron 3 | Major components which govern the dynamic equilibrium of Earth’s natural systems and determine habitability for life | System Output |

Table 2: Variables to be considered for a sustainable civilization from subunit I of the planetarian framework (Source: Goldson,2020)

| Subunit I Nodes | Descriptors of dodecahedron 2 nodes – Civilization designed infrastructure | Combination of subunit K nodes that form general components of Subunit I Node |

| I1 | Climate Change | Energy + Transport + Industry |

| I2 | Energy Usage and Provision | Energy + Industry + Residential/Commercial |

| I3 | Building and Utilities Use | Energy + Population + Residential/Commercial |

| I4 | Reproduction | Energy + Population + Waste |

| I5 | Resource Use and Consumption | Energy + Transport + Waste |

| I6 | Ecocurrency = True cost | Transport + Commons + Chemical Pollution |

| I7 | Circular Economy | Waste + Commons + Transport |

| I8 | Biodegradability and Landfills | Waste + Commons + Food |

| I9 | Freshwater Use | Waste + Population + Food |

| I10 | Inequality and Integration | Population + Food + Human Settlements/Buildings |

| I11 | Nation States | Population + Residential/Commercial + Human Settlements/Buildings |

| I12 | Global Governance | Biosphere + Residential/Commercial + Human Settlements/Buildings |

| I13 | Renewability and Sustainability | Industry + Biosphere + Residential/Commercial |

| I14 | Healthcare, Research and Medicine | Industry + Biosphere + Residential/Commercial |

| I15 | Work and Labour | Transport + Industry + Chemical Pollution |

| I16 | Agriculture (AFOLU) | Matter/Materials + Biosphere + Chemical Pollution |

| I17 | Land and Property Ownership | Matter/Materials + Biosphere + Human Settlements/Buildings |

| I18 | Nutrition and Diet | Matter/Materials + Food + Human Settlements/Buildings |

| I19 | Conservation | Matter/Materials + Commons + Food |

| I20 | Corporate Regulation | Materials + Commons + Chemical Pollution |

Table 3: Largescale components of civilization from subunit K of the planetarian framework (Source: Goldson,2020)

| Subunit K Node Designations | Descriptors – Icosahedron 2 – Human and environmental physical systems |

| K1 | Energy |

| K2 | Waste |

| K3 | Transport |

| K4 | Industry |

| K5 | Residential and Commercial |

| K6 | Population |

| K7 | Food |

| K8 | Matter and Materials |

| K9 | Commons |

| K10 | Toxic Pollutants |

| K11 | Biosphere and Carbon Sinks |

| K12 | Human settlements and buildings |

Policy suggestions:

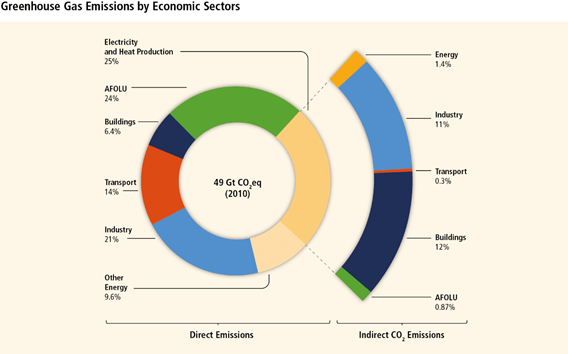

- Energy production, usage and provision: As can be seen in image 1 this sector has the largest share of global GHG emissions at 25% (IPCC,2014). We must shift to non-fossil fuel sources of energy faster. This sector effects the “other energy” sector as it mainly includes emissions from fossil fuel retrieval, processing and distribution which could save almost 10% GHG emissions just by itself.

Image 1: Greenhouse gas emissions by economic sector (Source: IPCC,2014)

- Industry: This being the second largest contributer to GHG emissions as seen in image 1 we could reduce large amounts of emissions by minimising industry to only essential industrial production of goods. Reducing industrial output so drastically would result in the loss of many jobs but this could be resolved if we implement recommendations that the total number of hours worked of the average employee should be reduced to around 21 hours per week (Coote,Franklin and Simms,2010) or follow a 4 day work week policy (Catlin,1997). The introduction of variable working hours could take into account a lifetime’s worth of working hours as being averaged to be 21 hours per week from ages 16 to 66 and once that amount has been served the citizen can retire to claim a universal basic income or receive greater incentives to stay in the workforce.

- Circular economy: Global economies would transform to follow the template of “doughnut economics” (Raworth,2017).

- Matter and materials: Only the mining and extraction of natural resources would be for necessary industries such as natural materials for construction, machinery, tools, textiles, hygiene, sanitary or cosmetics manufacturing etc.

- Transport: Another large portion of GHG emissions come from the transport sector as shown in image 1. If we were to reduce transport to that of only essential needs such as emergency service vehicles or those that run on “clean and green” energies such as electric cars, buses, coaches and trains we could reduce transport’s GHG emissions. The developed world’s system of the “just in time” delivery model is largely run by diesel powered trucks carrying heavy goods such as foods, household machinery and furniture. These trucks are not easily replaced by battery powered trucks because the batteries required are large and heavy in order to produce the same horsepower that combustion engines can (Kaufmann and Moynihan,2019). So, until electric trucks are able to enter the transport market or we can shift to a largely local economy, we will rely on diesel trucks. Drastic cuts will include taking combustion engine powered cars off the roads and cutting aviation flights, freight trains and shipping down to only essential transportation needs. With the massive industrial sector contraction proposed in this policy brief we would reduce the need for commuting and we should aim to have only electric powered cars and buses on the roads.

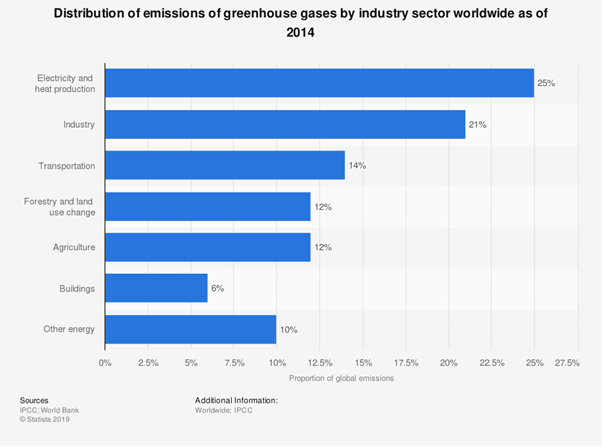

- Agriculture: Our current western food production models rely heavily on fertilisers which generate large GHG emissions during their production (Zhou et al.,2019). Moving to regenerative agriculture and no tilling methods of farming will not only reduce GHG emissions but also protect soils as a precious carbon sink (Marshall,2015). We should also hope to shift to a more locavore-based diet including the development of urban agriculture and adopting food sources such as backyard chickens in city suburbs for protein and eggs. Expecting to feed current city populations on urban agriculture by using all available green land is unrealistic and we should try to minimise food deliveries by diesel powered trucks and so an exodus of large numbers of city dwellers to rural regions will further aid in minimising GHG emissions. A diet that is lower in animal products will also reduce GHG’s emissions such as methane from enteric fermentation of ruminants. A related and equal portion of GHG output to that of agriculture comes from forestry and other land use (FOLU) as shown in image 2. This includes deforestation and the conversion of forest into agricultural land. Halting this deforestation could be achieved through the proposed transnational bioregional distributism. If such a proposal fails and no diplomatic resolution is forthcoming other traditional punitive political strategies could be used such as trade embargoes or as a last resort it may require global military intervention because our rainforests are so vital that they are worth fighting for.

Image 2: Greenhouse gas emissions by sector showing Forestry and land use change emissions separate from agricultural emissions (Source: Statista,2019)

- Residential and commercial: This sector contributes 6.4% of total global GHG emissions as shown in image 1, mainly due to onsite energy generation and fuels used for the heating of buildings, heating water and cooking. Reducing residential energy usage could involve the introduction of local food kitchens in all regions so that foods can be refrigerated, frozen and cooked on a larger scale which increases efficiency, reduces personal energy usage and helps citizens eat a plant rich diet. The possibility of removing the need for refrigerators in many households can answer the call for better global refrigerant management which is hailed in one paper as the number one method to combat climate change (Hawken,2017;Nash,2019).

In this future world without publicly available flights and fossil fuelled transportation we should desire to provide all citizens of the world the opportunity to become global citizens and experience the world’s varying cultures, climates and landscapes. This could be achieved by creating large networks of highways which are provided with electric vehicle battery charging stations at appropriate locations spanning entire continents. Fleets of electric coaches could be utilised to allow the mass transport of groups across these distances which could enhance the resilience of any given population’s ability to make emergency evacuations from the effects of climate change such as floods, droughts, crop failures and wildfires whilst still limiting GHG emissions. This infrastructure could even further mitigate effects of climate change and reduce GHG’s by moving large numbers of healthy individuals up and down continents according to seasonal demands for energy such as heating and cooling. With the elimination of summer tourism leaving large numbers of abandoned hotels due to limiting unessential aviation, these could provide accommodation for those escaping cold winters. The derelict office buildings left from minimising industrial operations could be repurposed as urban farming centres or to accommodate continental neighbours that are escaping dry and hot summers. This would form a network of minimalist nomads that could be a new source of seasonal labour that could help in harvesting crops at the end of summers or sewing new crops at the end of winters as simple examples. - Freshwater availability and usage: This would dictate the movements of minimalist nomads and the capacity to support climate refugees.

- Resource use and consumerism: The move away from mass production of consumer goods and consumerism will reduce GHG’s and preserve materials for future generations.

- “Ecocurrency”: This would be a new currency which is based on a “true cost accounting” of resources and the energy used to provide goods and services including their environmental impact (ecounit,2012). Existing corporations are not currently held accountable for the true cost of natural resource extraction and they reap huge profits by stealing these resources from future generations. The well-being of future generations (Wales) act 2015 serves as legislation which could support such an ecocurrency.

This ecocurrency would be non-exchangeable with existing currencies and by introducing a deflation rate on these over a fixed period would force those with wealth to invest into any of the new green initiatives and policies suggested here. This would provide an investment return in the form of this new ecocurrency. - Corporate regulation: Any companies producing goods and providing services would have caps placed on the profits they could acquire per unit of the capital sold to consumers. A transparency and responsibility for corporate activities to protect the environment and life on earth would include the limiting, safe handling and elimination of toxic pollutants where possible.

- Land and property ownership: New rules are required for the ownership of land and property that would seek to change the current renting model which is the number one passive income source and leads to property monopolies (Piketty,2013). The current mortgage and inheritance models allow for wealth to be consolidated upon and maintained in small circles of dynasties which contributes to the wealth inequality in the world (McElwee,2014).

Limiting the construction of new human settlements and building projects which use cement and timber will reduce GHG emissions. The retrofitting industry for energy efficient buildings would require large additional resources for training a new labour workforce to adapt existing buildings and help in the construction of new energy efficient eco-friendly buildings. - Research, healthcare and medicine: Research institutes should divert intellectual and material resources to provide efficiency improving methods and technologies to combat climate change. Healthier populations from healthier diets and more active lifestyles should alleviate pressure on health services and decrease their carbon footprint.

- Population: Limits must be set on family sizes and birth rates, particularly for countries that have the highest global share of GHG emissions. Having fewer children is stated as the number one personal action to decrease your personal carbon footprint being 30 times more effective per child than any other action (Wynes and Nicholas,2017).

- Inequality and integration: Creating a form of global citizenship whereby people can cross countries and continents via the renewable electricity powered vehicles driven over superhighways. Global citizenship education and the adoption of human rights laws would be required for any city, state or country to be initiated into this planetarian network of safe havens for communities to live in harmony with each other and their environment.

- Nation States: Despite the creation of global citizenship, each nation and region should maintain a certain sovereignty and cultural identity. This is because humans are territorial and by sticking to a 70% majority of each region’s cultural demographic will prevent discontent of people based on a threat of marginalisation. This figure of 70% is based on research showing that a minority of 25% or more is the tipping point to significantly alter the dynamics of the majority (Centola et al.,2018). But with birth rates fixed, such ratios would remain static and arguments based on marginalisation of pre-existing majorities would be obsolete and discourage intolerance and incitement to hatred.

Some nations have more work to do in becoming more sustainable such as those that have the highest percentages of their population living in cities. In contrast countries such as China and India have large portions of their populations living rurally of 41% and 66% respectively (UN,2019, The World Bank,2018). China as a country only became fully electrified by 2015 (Gang,2017). Thus, most Chinese rural populations still use off grid and mainly renewable methods of cultivating, harvesting, storing and cooking of food.

The sharing of natural resources equitably between nations would create an eco-economy where a nation’s comparative wealth is not determined by the natural resources that it’s land holds. - The commons: Efforts to increase conservation of the biosphere and carbon sinks such as those in table 4 are essential tools to combat climate change. Planting trees globally and specifically reforesting tropical rainforests are vital to restore equilibrium to the planets ecosystem support systems. Developed nations can help developing nations in this endeavour by setting up renewable energy supplied bases in and around rainforests, equipped with off-road electric vehicles to carry out this large-scale task and minimise GHG emissions whilst doing so.

Table 4: Categories of global carbon sinks and how they are affected by climate change

| Green carbon sinks – forests, terrestrial plants and soils |

| Forests and plants: With increased deforestation and forest dieback we see less CO2 absorbed by photosynthetic plants and trees. This allows atmospheric CO2 to rise which increases temperatures further and causes more forest dieback. Forest dieback contributes to precipitation reduction, firstly, by the biophysical feedback of reduced forest cover reducing evaporative water recycling. Secondly through the biogeochemical feedback by the release of CO2 adding to global warming. There is also a physiological forcing whereby rising CO2 forces stomatal closure which is the site of the plant through which gaseous exchange occurs (Betts et al,2004). Forests and terrestrial plants absorb carbon through a phytolithic sequestration process which is coupled to the biogeochemical silicon cycle. Silicon fertilizers can enhance carbon uptake (Song et al,2017). |

| Soils: Soils contain more carbon stores than all terrestrial vegetation and the atmosphere combined (Batjes,2016). Intensive agriculture from overgrazing and tilling contributes to depleting this vital carbon sink which could be managed better with regenerative agriculture methods (Marshall,2015). |

| Blue carbon sinks – Oceans and coastal ecosystems |

| Oceans: The solubility pump describes the process of atmospheric CO2 dissolving in seawater and it is the primary mechanism of CO2 uptake in ocean waters (Lade et al,2018). The solubility of CO2 in seawater decreases with increasing water temperature and thus with less CO2 absorbed there is increased heating which further reduces seawater CO2 solubility. The biological pump is that which describes the ocean life which sequesters carbon through the food web. An essential part played in this food web is that of phytoplankton which absorbs carbon into their shells. Ocean acidification, which increases with the increased amount of CO2 absorbed, reduces the ability of phytoplankton to thrive and form the carbonates needed for their shells thus reducing their numbers and sequestration capacity. |

| Coastal ecosystems: Mangrove forests along the coasts are also a carbon sink which if lost to sea level rise would reduce CO2 absorption and create a feedback loop (Wilson,2017). |

| Teal Carbon sinks – Freshwater wetlands |

| Wetlands: Wetlands hold a disproportionately large amount of carbon when compared to other soils. They only account for 5-8% of the earth’s land surface yet hold between 20-30% of total soil carbon (Nahlik & Fennessy,2016). |

18. Global Governance: The United Nations would serve as the most appropriate organisation to negotiate and approve such large scale multinational political, economic, environmental and social policies. The conference of the parties is the largest and most inclusive stage for deliberation on environmental issues and the policies. The policies proposed here could be raised and debated upon at this global forum. Currently the IPCC is considered as the world’s foremost authority on climate change issues and is used by policymakers to set their future policies. Their models are to be questioned though as their predictions on global temperature increases have been consistently too conservative and their datasets do not include the dangerous factors of positive feedback loops (Spratt & Dunlop,2018). This data is excluded on the grounds that not enough knowledge is known to quantify these feedback loops but they pose such a threat that if ignored could push us past a point of no return and cause climate catastrophe. These feedback loops are listed in the planetarian framework in subunit Q and shown in table 5.

Table 5: Positive Feedback loops and Earth’s environmental systems which are affected by such feedback loops from subunit Q of the planetarian framework (Source: Goldson,2020)

| Subunit Q Nodes | Descriptors of dodecahedron 3 nodes – Positive Feedback loops and Earth’s environmental systems which are affected by such feedback loops |

| Q1 | Green house gas concentrations in the atmosphere |

| Q2 | Forest Dieback weakens the ecosystem leaving it more vulnerable to further dieback |

| Q3 | Forest Fires spreading to human settlements increasing carbon dioxide emissions |

| Q4 | Polar ice caps, sea ice and glacier melt reduces surface albedo and increases sea level |

| Q5 | Melting of permafrost and methane hydrates under sea releasing potent GHG methane into the atmosphere |

| Q6 | Watervapour in the atmosphere as a green house gas |

| Q7 | Migration of tropical clouds towards poles, Unpredictable changes to monsoon seasons |

| Q8 | Jet streams – Polar Cell, Ferrel Cell, Hadley Cell |

| Q9 | El nino and La nina oceanic phenomena |

| Q10 | Thermohaline circulation disruption due to decreased water salinity |

| Q11 | Aquifer and water table depletion |

| Q12 | Increased carbon dioxide can cause stomatal closure in leaves which limits gaseous exchange and decreases the uptake of further carbon dioxide |

| Q13 | Rainforest hydrological cycle, transpiration from trees creates microclimate that is self sustaining and recycles water in that ecosystem |

| Q14 | Boreal Forests as carbon sinks |

| Q15 | Mangrove forests as carbon sinks |

| Q16 | Wetlands and Peat bogs as carbon sinks |

| Q17 | Soil erosion as soil is a vital carbon sink eg. Overgrazing, tilling |

| Q18 | Rainforest Land Coverage as a carbon sink |

| Q19 | Ocean biological pump – eg. Phytoplankton as a carbon sink and oxygen producer |

| Q20 | Ocean solubility pump – beyond carbon dioxide saturation it can no longer absorb it |

Summary:

Existing global attempts to devise goals and set policies to prevent climate disaster have shown little efficacy and are not aggressive enough. The continued acceleration of increasing global temperatures and GHG concentrations in the atmosphere demonstrates the failure of these efforts. The policy’s proposed here offer a more stringent yet stark approach to resolving the crisis.

Negative social implications from these policies which are not explored in this policy brief could be ameliorated if they are anticipated and researched ahead of time to develop strategies for a smoother transition away from our current global operating model.

References:

Batjes, N.H. (2016) Harmonized soil property values for broad scale modelling (WISE30Sec) with estimates of global soil carbon stocks. Geoderma 269 61-68

Betts, R. Cox, P. Collins, M. Harris, P.P. Huntingford, C. Jones, C.D. (2004) The role of ecosystem-atmosphere interactions in simulated Amazonian precipitation decrease and forest dieback under global climate warming. Theoretical and applied climatology. 78(1-3) 157-175

Catlin, C. S. (1997) Four-day work week improves environment Journal of Environmental Health; Denver Vol. 59, Iss. 7, 12-15.

Centola, D. Becker, J. Brackbill, D. Baronchelli, A. (2018) Experimental evidence for tipping points in social convention Science Vol 360, Iss. 6393 pp. 1116-1119

Cheng, L., et al., (2020): Record-setting ocean warmth continued in 2019. Adv. Atmos. Sci., 37(2),137−142, https://doi.org/10.1007/s00376-020-9283-7

Coote, A. Franklin, J. and Simms, A. (2010) ’21 hours’ The New Economics Foundation. Available at: https://neweconomics.org/uploads/files/f49406d81b9ed9c977_p1m6ibgje.pdf

Ecounit (2012) Human and Resources economic system manifesto. Available at: http://ecounit.org/files/ekounit.pdf https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3Vh_gnRrETk

Gang, H. (2017) Three lessons from China’s effort to bring electricity to 1.4 billion people. Available at: https://www.chinadialogue.net/article/show/single/en/9934-Three-lessons-from-China-s-effort-to-bring-electricity-to-1-4-billion-people

Goldson, L. (2020) The Planetarian Framework of Civilization – Updated and Explained. Where to go next? Available at: https://wordpress.com/block-editor/post/planetarian85.music.blog/106

Hawken, P. (2017) Drawdown the most comprehensive plan ever proposed to roll back global warming, USA, Penguin books

IPCC, (2014): Summary for Policymakers. In: Climate Change 2014: Mitigation of Climate Change.Contribution of Work-ing Group III to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Edenhofer, O., R. Pichs-Madruga, Y. Sokona, E. Farahani, S. Kadner, K. Seyboth, A. Adler, I. Baum, S. Brunner, P. Eickemeier, B. Kriemann, J. Savolainen, S. Schlömer, C. von Stechow, T. Zwickel and J.C. Minx (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA

IPCC SR15 (2018), Global warming of 1.5°C, Masson-Delmotte, V. Zhai, P. Pörtner, H. O. Roberts, D. Skea, J. Shukla, P. R. Pirani, A. Moufouma-Okia, W. Péan, C. Pidcock, R. Connors, S. Matthews, J. B. R. Chen, Y. Zhou, X. Gomis, M. I. Lonnoy, E. Maycock, T. Tignor, M. Waterfield, T (2018) IPCC, 2018: Summary for Policymakers. In: Global warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the impacts of global warming of 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels and related global greenhouse gas emission pathways, in the context of strengthening the global response to the threat of climate change, sustainable development, and efforts to eradicate poverty World Meteorological Organization, Geneva, Switzerland, 32 pp

Read, R. O’riordan, T. (2017) The precautionary principle under fire. Environment science and policy for sustainable development. 59(5) 4-15

Kaufmann, J. Moynihan, R. (2019) ‘Electric trucks like the Tesla Semi are ‘pointless both economically and ecologically,’ according to a vehicle-tech expert’ Business Insider. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/this-expert-says-tesla-semi-is-economically-and-ecologically-pointless-2019-2?r=US&IR=T

Lade, S.J. Donges, J.F. Fetzer, I. Anderies, J. M. Beer, C. Correll, S.E. Gasser, T. Norberg, J. Richardson, K. Rockstrom, J. Steffen, W. (2018) Analytically tractable climate-carbon cycle feedbacks under 21st century anthropogenic forcing. Earth.syst.Dynam. 9 507-523

Marshall, L. (2015) Organic-plus? Natural foods merchandiser; Badle 36(10) 23-24, 26

Mcelwee, S (2014) ‘THE INHERITANCE OF LOSS America’s new wealthy have so little to offer society’ Quartz. Available at: https://qz.com/196575/to-get-rich-forget-entrepreneurship-and-marry-wealthy/

Nahlik, A.M. Fennessy, M.S. (2016) Carbon storage in US wetlands. Nature Communications 7: 13835

Nash, B. (2019) #01 Refrigerant Management. Available at: https://barnabythinks.com/2019/05/19/01-refrigerant-management/

NOOA (2020) Assessing the Global Climate in 2019. Available at: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/news/global-climate-201912

NOAA, ESRL, Global Monitoring Division (2020) Available at: https://www.esrl.noaa.gov/gmd/ccgg/trends/index.html

National snow and ice data centre, (2020) That’s a wrap: A look back at 2019 and the past decade. Available at: https://nsidc.org/arcticseaicenews/2020/01/thats-a-wrap-a-look-back-at-2019-and-the-past-decade/

Piketty, T. (2013) Capital in the twenty-first century Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press, 2014 Translated by Goldhammer, A.

Raworth, K. (2017). Doughnut economics: seven ways to think like a 21st-century economist. New York, United States: Random House. ISBN 978-184794138-1.

Spratt, D. Dunlop, I. (2018) What Lies Beneath. The understatement of existential climate risk. Breakthrough. National centre for climate restoration. Available at: https://docs.wixstatic.com/ugd/148cb0_a0d7c18a1bf64e698a9c8c8f18a42889.pdf

Statista (2019) Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/270723/distribution-of-global-greenhouse-gas-emissions-by-sector-worldwide/

Song, Z. Liu, H. Stromberg, C.A.E. Yang, X. Zhang, X. (2017) Phytolith carbon sequestration in global terrestrial biomes. Science of the total environment 603-604: 502-509

The World Bank (2018) Available at: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.RUR.TOTL.ZS?most_recent_value_desc=true

United Nations (2019) Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division World Urbanization Prospects: The 2018 Revision (ST/ESA/SER.A/420). New York: United Nations

Wilson, R. (2017) Impacts of climate change on mangrove ecosystems in the coastal and marine environments of Caribbean small island developing states (SIDS). Caribbean marine climate change report card; science review: Science Review 2017 60-82

Wynes, S, Nicholas, K. A. (2017) The climate mitigation gap: education and government recommendations miss the most effective individual actions, Environmental Research Letters, 12(7)

Zhou, X. Passow, F.H. Rudek, J. von Fisher, J.C. Hamburg, S.P. and Albertson, J.D. (2019) Estimation of methane emissions from the U.S. ammonia fertilizer industry using a mobile sensing approach. Elem Sci Anth, 7(1), p.19. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1525/elementa.358