[elective essay, incomplete, without references, not much structure but useful]

In creating large food halls and food kitchens by converting retail parks, industrial estates and shopping centres and highstreets, we can incorporate places which not only provide healthy meals but also provide access to food and personal essential supplies for residential storage, use and consumption. These infrastructures with existing car parking could serve local communities that are nearby so walking and cycling to these hubs of essential services is possible with waiting areas outfitted with clean cooling and clean heating which could be built on existing car parking areas. Meals and supplies could also be made available with an electric vehicle drive -thru which could allow for provisions and deliveries made to a larger community from those that live farther away. A wide range of services can be provided at these community hubs such as health services and education which together, with the provision of plant-rich meals, this strategy can achieve the four top objectives of Project Drawdown (PD) which can potentially create the largest greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions reductions (Hawken,ref?). These are food waste; health and education (promotes lower birth rates and population size stabilization); plant-rich diets; and refrigerant management (RM) as shown in table 1.

A list of PD’s solutions which food hubs can facilitate their introduction into the design of our actions to mitigate, adapt to, and be resilient to CC are given in table 1. The associated CO2 equivalent GHG emissions reductions are given for each intervention as a range between two scenarios, with scenario 1 in line with a 2 degree C temperature rise by 2100 and scenario 2 in line with a 1.5 degree C rise by 2100. The implementation of food hubs with an integrated clean cold chains (CCC) and clean heating will allow society a greater likelihood of achieving the ambitious targets set by scenario 2. These figures are based on projected global emissions and therefore will differ significantly on the ecological, economic, political, and social context where they are introduced.

This strategy of centralizing food storage (particularly refrigerated goods), preparation, cooking and consumption increases the efficiency of various other systems in society. Alternative refrigerants such as ammonia and carbon dioxide (CO2) with low global warming potentials (GWPs) and which are not ozone depleting substances (ODSs) could be used in large cold stores for food to be cooked daily and to be supplied to citizens. To further enable the efficacy of centralised refrigeration, the use of new technologies which draw CO2 from the atmosphere could be used as a source of the refrigerant and not just lowering GHG emissions but also reducing the amount of CO2 in the atmosphere. The large scale of refrigeration and cooling for such an operation would be required to create a large enough impact to mitigate climate change (CC). A phrase used recently is that being alive at this time of human history gives people “front row seats” to such a remarkable, yet dangerous period where civilizations’ past actions have become so significant so as to alter the very planet we live on. These food hubs with clean cooled and heated waiting areas literally provide these very seats for humans to witness the unfolding events of human induced CC. With the terrifying consequences of inaction on CC, this large-scale intervention can provide safety for communities that engage the issue and build resilience to outcomes such as intermittent energy supply due to extreme weather events or decisions by national leaders to limit energy distribution so that its consumption is lowered to drastically reduce GHG emissions.

Table 1: A list of solutions given in PD which food hubs can facilitate their implementation and their corresponding GHG emissions reduction potentials given as Gigatons of CO2 equivalent reduction/sequestered. Source: (Hawken,ref?)

| Solution | Grouping | Scenario 1~ | Scenario 2~ |

| Reduced Food waste | Food supply chain and lifecycle | 87 | 95 |

| Health and education | Population size and health | 85 | 85 |

| Plant-rich diets | Food supply chain and lifecycle | 65 | 92 |

| Refrigerant management | Food supply chain and lifecycle | 58 | 58 |

| Tropical-forest restoration | Land sinks | 54 | 85 |

| Onshore wind turbines | Energy supply and transport | 47 | 148 |

| Alternative refrigerants | Food supply chain and lifecycle | 44 | 51 |

| Utility-scale solar photovoltaics | Energy supply and transport | 42 | 119 |

| Improved clean cookstoves | Food supply chain and lifecycle | 31 | 73 |

| Distributed solar voltaics | Energy supply and transport | 28 | 69 |

| Silvopasture | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 27 | 42 |

| Peatland protection and rewetting | Land sinks | 26 | 42 |

| Tree plantations (on degraded land) | Land sinks | 22 | 34 |

| Temperate forest restoration | Land sinks | 19 | 28 |

| Concentrated solar power | Energy supply and transport | 19 | 24 |

| Insulation | Clean heating and buildings | 17 | 19 |

| Managed grazing | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 16 | 26 |

| Led lighting | Clean heating and buildings | 16 | 18 |

| Perennial staple crops | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 15 | 31 |

| Tree intercropping | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 15 | 24 |

| Regenerative annual cropping | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 15 | 22 |

| Conservation agriculture | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 13 | 9 |

| Abandoned farmland restoration | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 12 | 20 |

| Electric cars | Energy supply and transport | 12 | 16 |

| Multistrata agroforestry | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 11 | 20 |

| Offshore wind turbines | Energy supply and transport | 10 | 11 |

| Methane digesters | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 10 | 6 |

| Improved rice production | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 9 | 14 |

| Indigenous peoples’ forest tenure | Land sinks | 9 | 13 |

| Bamboo production | Land sinks | 8 | 21 |

| Alternative cement | Clean heating and buildings | 8 | 16 |

| Hybrid cars | Energy supply and transport | 8 | 16 |

| Carpooling | Energy supply and transport | 8 | 4 |

| Public transit | Energy supply and transport | 8 | 23 |

| District heating | Clean heating and buildings | 6 | 10 |

| Geothermal power | Clean heating and buildings | 6 | 9 |

| Forest protection | Land sinks | 6 | 9 |

| Recycling | Food supply chain and lifecycle | 6 | 6 |

| Biogas for cooking | Food supply chain and lifecycle | 5 | 10 |

| Efficient trucks | Food supply chain and lifecycle | 5 | 10 |

| Efficient ocean shipping | Food supply chain and lifecycle | 4 | 6 |

| High efficiency heat pumps | Clean heating and buildings | 4 | 9 |

| Perennial biomass production | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 4 | 7 |

| Solar hot water | Clean heating and buildings | 4 | 14 |

| Grassland protection | Land sinks | 3 | 4 |

| System of rice intensification | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 3 | 4 |

| Nuclear power | Energy supply and transport | 3 | 3 |

| Bicycle infrastructure | Energy supply and transport | 3 | 7 |

| Biomass power | Energy supply and transport | 3 | 4 |

| Nutrient management | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 2 | 12 |

| Biochar production | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 2 | 4 |

| Landfill methane capture | Food supply chain and lifecycle | 2 | -1.6 |

| Composting | Food supply chain and lifecycle | 2 | 3 |

| Waste-to-energy | Clean heating and buildings | 2 | 3 |

| Small hydropower | Energy supply and transport | 2 | 3 |

| Walkable cities | Energy supply and transport | 1 | 5 |

| Sustainable intensification for smallholders | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 1 | 1 |

| Electric bicycles | Energy supply and transport | 1 | 4 |

| High speed rail | Energy supply and transport | 1 | 4 |

| Farm irrigation efficiency | Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 1 | 2 |

| Recycled paper | Food supply chain and lifecycle | 1 | 2 |

| Telepresence | Energy supply and transport | 1 | 4 |

| Coastal wetland protection | Land sinks | 1 | 1 |

| Coastal wetland Restoration | Land sinks | 1 | 1 |

| Water distribution efficiency | Water conservation | 1 | 1 |

| Green and cool roofs | Clean heating and buildings | 1 | 1 |

| Electric trains | Energy supply and transport | 0.1 | 0.65 |

| Micro wind turbines | Energy supply and transport | 0.09 | 0.13 |

Key: Yellow – Food supply chain and lifecycle. Grey – Population size and health. Green – Land sinks. Light Blue – Energy supply and transport. Pink – Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU). Red – Clean heating and buildings. Dark Blue – Water conservation.[cant find how to highlight in wordpress]

Taking the groupings of the solutions and noting similarities to some groupings we can define several strategy types with associated CO2 equivalent emissions savings as shown in table 2:

Table 2: The total carbon dioxide equivalent emissions reductions/sequestered by each main category from project drawdown

| 1.Refrigerant management and Alternative Refrigerants | 102 | 109 |

| 2. Food supply chain and lifecycle | 208 | 296 |

| 1. + 2. (Refrigerants + Food) = | 310 | 405 |

| 3. Energy supply and transport | 196 | 464 |

| 4. Agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) | 152 | 240 |

| 5. Land sinks | 149 | 387 |

| 4. + 5. (AFOLU + Land Sinks) = | 301 | 627 |

| 6. Population (health and education) | 85 | 85 |

| 7. Clean heating and buildings | 64 | 99 |

The use of onshore wind turbines is number 6 in PD’s list of solutions. The rollout of turbines would be advantageous to supply electricity for the food hubs as well as utility scale photovoltaics on the roofs of these complexes. A more secure supply would be required such as connection to nuclear electricity supply or the new opportunities that small modular nuclear reactors present to the energy generation sector. Refrigeration is one of the few processes that society depends upon which requires a constant supply of electricity. Therefore, by centralizing its function in society and protecting it with secure energy sources we can reduce our dependency on decentralised refrigeration in supermarkets and homes. Food hubs with large food cold stores could order and store produce to be delivered daily such that food is not stored for long before it is used for cooking and consumption.

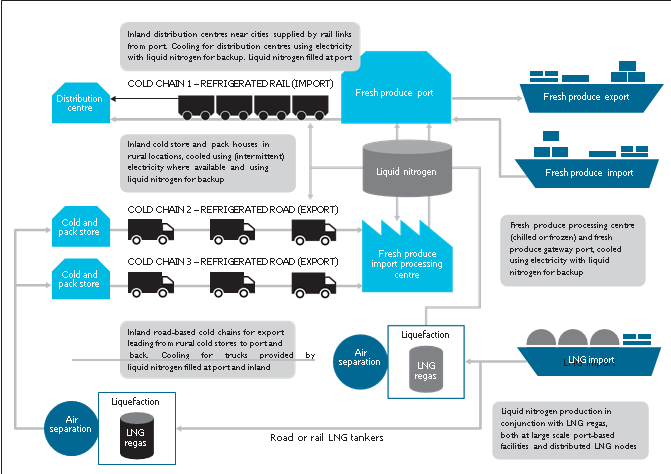

The introduction of clean cold chains (CCCs) removes steps from our existing cold chains and makes the stages of cooling more efficient and more environmentally friendly. New technologies have been developed and tested in the food transport sector such as the Dearman engine for transport refrigeration units (TRUs) that use liquid air (Liquid air energy network,2014). These CCCs make use of wasted heat energy from the regasification of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to create liquid nitrogen for use as a refrigerant in TRUs (Image 1). These clean TRUs have been tested for home delivery by UK supermarket chain Sainsburys (ref) and this type of use of waste energy is listed as number 44 and 57 of efficient trucks and for the use of waste heat in PD’s solution table, respectively.

Image 1: Recycling LNG waste cold to provide clean cold chain cooling Source: (Dearman,ref?)

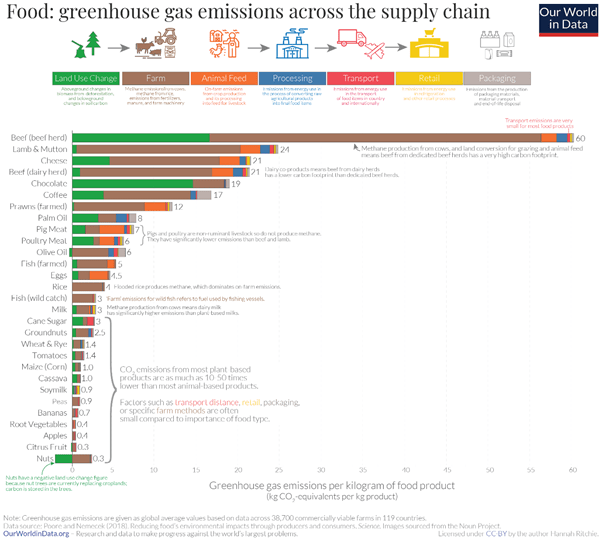

The food by lifecycle across the supply chain is shown in image 2. The GHG emissions from all stages of the supply chain is shown for different foodstuffs as a summation of emissions from land use change for farming, farming itself, animal feed, processing, transport, retail, and packaging. The solutions relating to the food supply chain and lifecycle are highlighted in yellow in table 1. Land use change includes deforestation for farmland mainly for grazing cattle as well as non-farming purposes. The halting of these actions and instead changing our current use of these land carbon sinks are highlighted in table 1 as the green items in the list. Food hubs can act as a training centre and deploy teams in electric vehicles to carry out restoration and protection projects for land carbon sinks. Those stages of the farming process as analysed by PD of which food hubs can facilitate are highlighted in pink. Food hubs facilitate these processes of land use change and farming by reducing food waste and thus reducing the need for higher yields from the farming sector. This means farmers can maintain or reduce yields and focus on carrying out more sustainable farming practices.

Image 2: GHG emissions across the food supply chain. Source (ref?)

It has been found that the choice of animal feed can alter the GHG emissions from ruminants (Ref?) in the form of belching and flatulence. A recent discovery is that by incorporating a species of seaweed known as Asparagopis Toxifarmis into beef cattle feed can reduce cattle methane emissions by up to 90% (ref?). The food lifecycle stages of processing, transport, retail, and packaging shown in image 2 can be addressed by clean cold food hubs as well as the other stages of refrigeration, recycling, food cooking and food waste (which is the second highest impact PD solution, second to combined RM and alternative refrigerants). By ordering and selecting foods for specific, planned, plant-rich food meals in food halls this centralised storage and refrigeration would be more energy efficient and lower food waste and allow a full and complete recycling of packaging, which itself would be reduced. The packaging of food accounts for 5% of GHG emissions in the global food supply chain (Ref?). Food hubs, halls and kitchens could dramatically reduce this figure as well as allow for the complete recycling of packaging which reduces strain on household waste collection. They can also allow for a more complete composting of foodstuffs as employees that prepare foods and consumers put waste foodstuffs into onsite food waste bins. Retail food outlets would sell a lower quantity of stock which requires expensive and often unrecyclable packaging to target consumers. The introduction of food hubs for consumer procurement and onsite consumption adds a new step in the food supply chain which replaces part of the sector provided by large supermarket chains and lowers home food storage needs and thus wastage.

As opposed to supermarkets which have rows of refrigeration units, most commonly multiplex rack systems, the food hubs could stack refrigerators vertically along rows that staff can access when stock is requested for pickup or for use in the food kitchens. This vertical stacking is a more efficient use of space than supermarket refrigerators that are designed for consumer safety in mind. Alternatively large, refrigerated rooms with shelving to store stock would be more efficient than supermarket refrigerated display cases. This type of stock pickup process described could be similar to the click and collect style of ordering or by filling in a form by pencil and paper as a system like that used in retail outlets such as Argos in the UK.

Globally, in 2006, there were 530,000 supermarkets containing more than 546,000 metric tons of refrigerants. 60% of refrigeration in the commercial sector uses the multiplex rack system, 33% for condensing unit systems and 7% for standalone or self-contained refrigeration systems (Ref?). Multiplex rack systems consist of racks of multiple compressors typically in an operation room which are linked to multiple display cases in the sales area using extensive piping. Standalone systems integrate all refrigerating components within their structures which account for 32 million units worldwide and an additional 20.5 million vending machines (ref?). By using alternative modes of access to refrigerated goods we can limit the GHG emissions associated with the manufacture, sale and transport of refrigerators which cuts the embodied energy required for their production and sale and their subsequent energy usage once in operation. The refrigerator sector globally is made up of 25% commercial refrigeration in the developed world, 15 % of commercial refrigeration in the developing world and 60% other refrigeration and air conditioning. The idea of community cooling hubs could make use of the extensive alternative refrigerants powered cooling systems through ventilation ducts to cool waiting areas on hot days and other spaces such as onsite computer server rooms and internet cafes for example.

Another example of using waste-to-energy would use the incineration of high GWP refrigerants (>2500?) as we phase out their usage in supermarkets, residential settings and air conditioners used in offices as we switch to a higher proportion of workers working from home via telepresence. There is an estimated 5687 kT of ozone depleting substances as refrigerants globally with 3070 kT in non-article 5 countries of the Montreal Protocol (eg. The EU), 2617 kT from article 5 countries (eg. India) with China having 1,200 kT of ODS alone. The waste heat used to incinerate refrigerants could be incorporated into district heating alongside geothermal and biomass sources which alone could reduce GHG emissions estimated at a possible 6-10 Gigatons of CO2 equivalent reduction in PD. Food hubs could also have their own onsite district heating source for use throughout the complex on cold days and provide the surrounding community with district heating. Items highlighted in red in table 1 pertain to clean heating and building solutions. As households in an urban environment, we all share a water, gas and electricity supply, so why not share a heat supply also?

Clean heating can include the energy used for cooking and hot water for bathing and washing dishes and utensils. There is also the embodied energy of all our personal household items such as ovens, microwaves, dishwashers, food appliances (eg. Blenders and food processors) and the utensils used in preparation and eating food. If we as households did not require such a numerous number of items related to food to prepare, cook, consume, clean, and ultimately replace multiple times within a lifetime; a large amount of energy would be saved if we also take into account the energy that companies use to sell all these goods in retail outlets and the creation, packaging and transport of goods for consumers.

The idea of food hubs and the threat of residential intermittent energy supply will encourage the uptake of residential renewable sources of energy such as solar and small wind turbines. The uptake of electric vehicles for those who have the financial capital to invest in them could increase for homes that want to travel to food hubs, halls and kitchens as petrochemical reliant combustion engines are phased out. Incentives to remove refrigerants from residential settings (which would be ineffective for refrigeration of food in the eventuality of intermittent energy supply) could be created in the form of allowing removal of high GWP refrigerants from home appliances to be used in incineration, or the entire appliances taken in exchange for a reduced cost of installing residential renewables. If residents are healthy and fit enough to travel to nearby food hubs, halls and kitchens they could offer their combustion engine vehicles for exchange of reduced cost home renewables. These cars can be retrofitted into electric vehicles for a minority and the rest would likely be recycled and scrapped at a rate feasible for the operation capacity. The green initiatives associated with this type of urban living are described in PD and highlighted in table 1 as the light blue solutions.

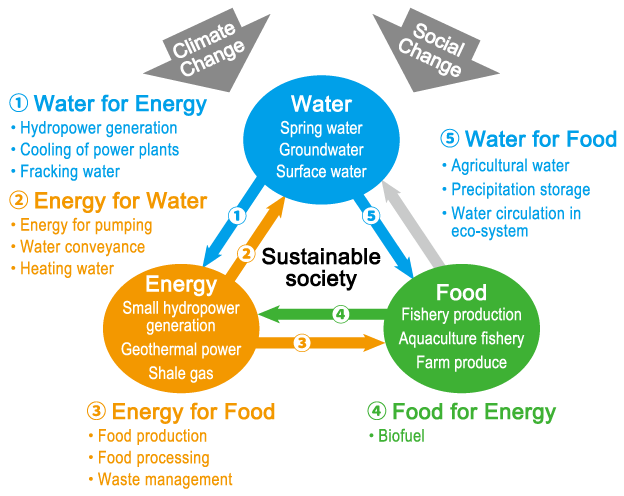

Image 3: The food energy water nexus and the interdependencies between each sector

The food, energy, and water (FEW) nexus (shown in image 3) is embedded within the set of solutions given by PD and can be facilitated by the creation and use of food hubs, halls and kitchens. The solutions in table 1 highlighted in light blue and red are those pertaining most to energy whilst those highlighted in yellow, green, and pink pertain to food. The single items in grey and dark blue of education and health and water distribution efficiency, respectively, correspond to population size and water availability. Water conservation is inherent in many of these solutions as an indirect consequence of actions taken. Outside of these solutions there is a more direct way of water management which is by moving large numbers of people seasonally so that clean cooling and clean heating is also emphasised. The idea of clean cooling and clean heating is achieved directly with three multiplicative factors that are (1.) the reduction in the need for cooling/heating, (2.) increased efficiency and (3.) use low carbon electricity to supply these systems. These factors are multiplicative and not additive, so the larger the change in the initial variable of demand, the larger the carbon emissions reductions that are achieved. If people are moved seasonally from cold regions during winter times to locations with a warmer climate the demand for heating is reduced. The same is true for moving people with hot climates during summertime to cooler regions to reduce the demand for cooling. These strategies are both tied into water conservation because during a hot summer in warm climes the water stress is more of a threat. If there were minimalist nomads across our continents that travelled seasonally to spend 6 months at a time away from home and ferried across renewable electricity supplied superhighways in electric vehicles such as existing fleets of cars, buses and coaches or high-speed trains. The type of people most suited to this voluntary action are those with fewer ties to a region keeping them there such as jobs or dependent family members. Students are a good candidate since they can also study via distance learning for many courses and the UK has 2.38 million students as of 2019 (ref?). Moving millions of people across continents would require temporary homes for them to live in and adequate food supply. With the likelihood of having to end tourist aviation due to the high burden of GHG emissions this activity creates, there would be a very large stock of empty tourist resorts. If instead of the usual seasonal use of these during summer months they were inhabited by minimalist nomads during winter and then make use of large-scale food facilities and create food hubs, halls and kitchens in the regions we could support these temporary populations. By monitoring water availability of regions, we could calculate how many nomads any region could accept at any one time and adapt to changing circumstances in the event of unpredictable weather events like drought and severe storms by moving populations around via the superhighways.

Across the board, food hubs, halls and kitchens are a more efficient and effective system of dealing with the task of feeding a high-density population and communities via a complete integration of the water, energy food nexus to our solutions.