[Masters degree essay created June 2021]

Introduction:

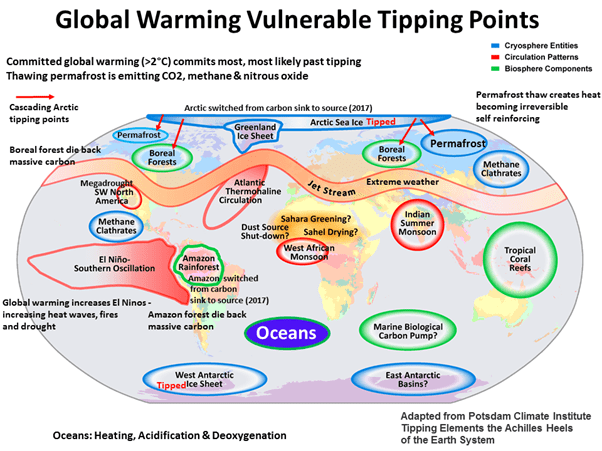

Ecosystems are dependent on the atmosphere to maintain a delicate balance of weather and variable climate conditions to thrive (Frank et al.,2015). Climate change (CC) is causing more extreme deviations from previously recorded weather patterns and this is creating instabilities in a wide variety of ecosystems and their accompanying biospheres (Frank et al.,2015). These hypothesised tipping points in globally interconnected ecological systems (Image 1), which if a threshold is crossed, could irreversibly devastate not just single ecosystems but negatively impact other connected ecosystems (Lenton et al.,2019).

Image 1: Global warming tipping points (Source: denman island climate action network,2021)

The main contributors to anthropogenic climate change (CC) are the greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2), methane, nitrous oxide and several classes of synthetic halogenated compounds which are substances that contain a halogen element in their structure such as fluorine, chlorine, bromine, iodine, or astatine. Within the halogenated gases class are an array of chemicals that possess the highest global warming potential (GWP) of any other known substances. Chlorofluorocarbons (CFC’s) and hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFC’s) have relatively low GWP values but are largely no longer used in industrial manufacturing due to their high ozone depleting potentials (ODP’s) thus them being phased out for use as mandated by the Montreal Protocol (MP) (Norman, DeCanio & Fan,2008). Other classes of halogenated gases include hydrofluorocarbons (HFC’s), perfluorocarbons (PFC’s), hydrofluoroolefins (HFO’s) and other potent GHG compounds such as sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) and Nitrogen trifluoride (NF3). These classes all belong to a separate class of halogenated compounds which do not contain chlorine but do contain fluorine and are defined as fluorinated gases, or F-gases for shorthand (Sovacool et al.,2021).

An important distinction between most F-gases and other GHG’s is that most of their emissions are fugitive emissions (meaning they escape or leak from their intended use), whereas most other GHG emissions are produced because of direct human activities (EPA,2014). GHG emissions which are by-products of human activities mean it could be possible to stop or drastically reduce them, such as fossil fuel burning and ruminant cattle farming. There is also potential to remove more CO2 from the atmosphere by reinforcing carbon sink capacities or removal using direct carbon capture technologies (Marcucci, Kypreos & Panos,2017). This distinction sets F-gases apart from other GHGs because their emissions are largely a waste product of industrial, commercial, agricultural, and domestic uses of the gases themselves, and once they are released into the atmosphere there is currently no means of extracting them.

Evidence, Analysis and Argument:

The biosphere and atmosphere interaction:

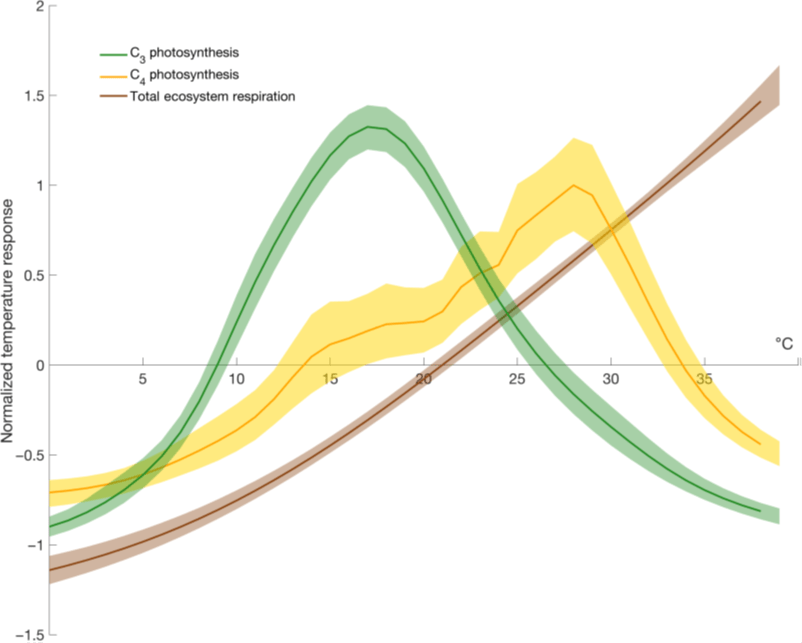

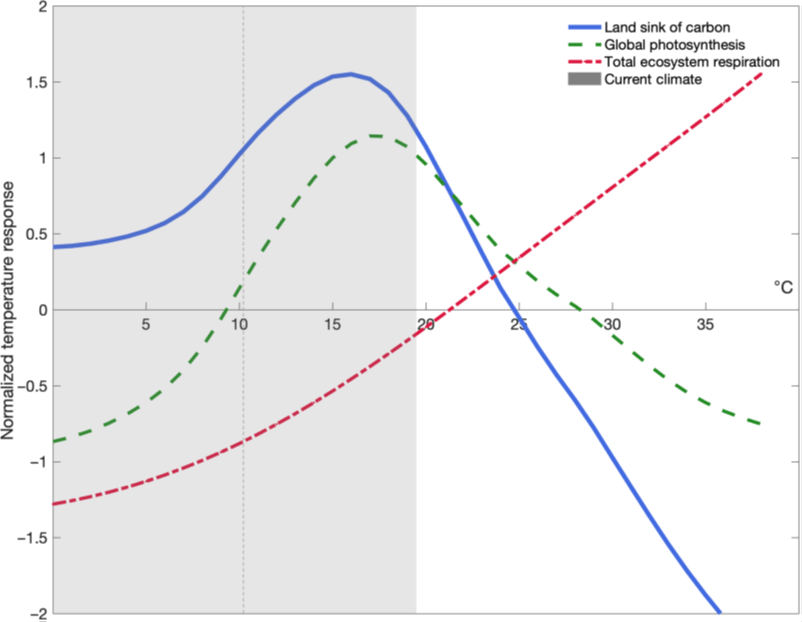

Human activities in rainforest ecosystems in the agriculture, forestry and other land use (AFOLU) sector contribute to the reduction of the global ecosystem services it provides (Roman-Cuesta et al.,2016). Many activities cause deforestation of the Amazon rainforest, such as logging, livestock farming, mining, oil drilling, and soy plantations. The global land carbon sink strength is a measure of the mitigation capacity of anthropogenic carbon emissions, which currently equates to approximately 30% (Duffy et al.,2021). Climate change also effects the land carbon strength capacity since global photosynthesis and respiration metabolic rates are temperature dependent and there are narrow optimum values for temperature ranges for photosynthetic ecosystems (Ma et al.,2017). Images 2 and 3 show that as temperatures increase, photosynthesis rates decline, and respiration rates increase for both C3 and C4 plants (most rainforest plants are C3 type with grasses and corn being C4 type plants for example). This has been modelled by the macromolecular rate theory which is based on variations in enzyme catalyzed processes such as the Krebs cycle or cytochrome pathways in leaf respiration (Liang et al.,2018).

Image 2: Photosynthesis and respiration rates of C3 and C4 plants versus temperature. (Source: Duffy et al.,2021)

Image 3: The temperature dependence of the terrestrial carbon sink (blue line) with photosynthesis of c3/c4 plants integrated as the green dashed curve and red dashed dotted line showing increasing respiration rates. Current climate ranges lie within the grey shaded box. (Source: Duffy et al.,2021)

This climate regulation service is predominantly provided by rainforests of the globe with the tropical rainforests of the Amazon accounting for ~50% of rainforests in the world (Qin et al, 2021). Degradation of the Amazon rainforest such as forest dieback from drought and natural wildfires accounts for 73% of the loss of aboveground biomass (Qin et al.,2021) and contributes significantly to the potential of the ecosystem switching from a carbon sink into a net carbon source (Covey et al, 2021). Amazon rainforest tipping points are estimated to occur at 4°C temperature rise and deforestation of 40% of forest area (Nobre et al.,2016).

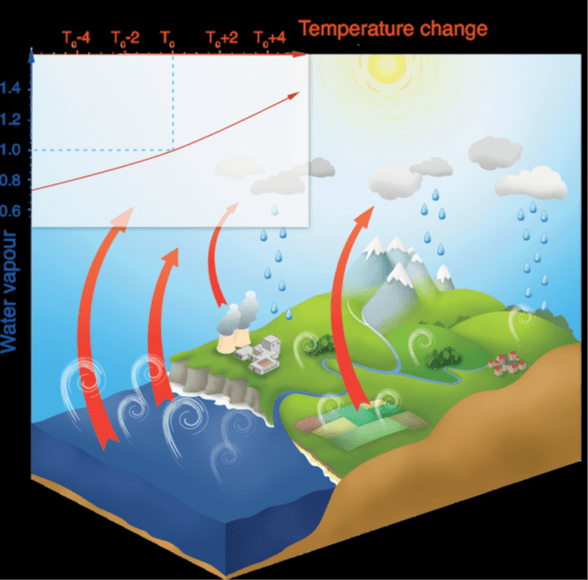

Atmospheric water vapor (H2O) is the largest contributor to the natural greenhouse effect as it is a GHG with around two or three times a greater contribution to the greenhouse effect relative to CO2 (IPCC 5AR WG1,2013). It is not considered as an anthropogenic gas but instead as a feedback agent partly because it resides in the troposphere for around 10 days before it condenses and falls as precipitation. The amount of H2O in the air is predominantly temperature dependent and with every extra degree of increase in atmospheric air temperature, there is a 7% increase in retention capacity in the atmosphere to hold H2O (IPCC 5AR WG1,2013). Other greenhouse gases such as CO2 effect the H2O content of the atmosphere as it’s presence is required to hold it in the atmosphere (IPCC 5AR WG1,2013). This process and the interaction of temperature and H2O is shown in image 4.

Image 4: The water cycle and it’s role in the greenhouse effect. The top left panel shows increases in atmospheric water vapour with increasing temperature. (Source: IPCC 5AR WG1,2013)

F-gases – Their management and emissions:

Existing global agreements to manage halogenated gases include the MP and it’s most recent amendment, the 2016 Kigali Accord (KA); the Kyoto Protocol; and the nationally determined emissions reduction pledges of the 2015 Paris Agreement. F-gas emissions are growing at a faster rate than any other class of GHG’s, especially in developing countries (EIB,2016). It is stated that sustained and comprehensive interventions are required to curb the uncontrolled growth of F-gas emissions or they could undo the progress of existing climate governance policies (Höglund-Isaksson et al.,2017).

The use of F-gases is growing at an aggressive rate which is expected to accelerate faster than economic growth rates (Durkee,2006). There are three main drivers of this acceleration (Sovacool et al.,2021) which are (1.) unanticipated effects of the MP, (2.) growth in the global demand for cooling, and (3.) loopholes in existing commitments.

- The switch from high ODP substances to other chemicals such as HFC’s and PFC’s was mandated by the MP. The climate benefits of ozone protection could be significantly offset by the projected emissions of HFC’s over the next decades (WMO,2014).

- Without mitigation actions, the growing demand for cooling and refrigeration from the growth of the middle classes in developing nations such as China and India, is projected to increase the consumption and resultant global emissions of HFC’s (Congressional Research Service,2020).

- The KA addresses the growth of HFC’s but does not include phasing out of other classes of halogenated gases and does not address emissions from ‘banks’ of halogenated gases (UNEP,2019). It commits to reduce HFC consumption and production by 80-85% by the late 2040’s and there are exemptions for countries with high ambient temperatures (Roberts,2017).

Present day emissions of HFC’s represent just 1% of global GHG emissions but if left unabated their growth could reach 19% of GHG emissions by 2050 (EIB,2016). Global adherence with the KA is expected to remove 61% of global baseline HFC emissions over the period 2018-2050 (Höglund-Isaksson et al.,2017). Investing in energy efficient refrigeration and air conditioning (AC) could possibly double this mitigation through the reduction of other GHG emissions produced by electricity consumption (Shah et al.,2015).

F-gas uses and applications:

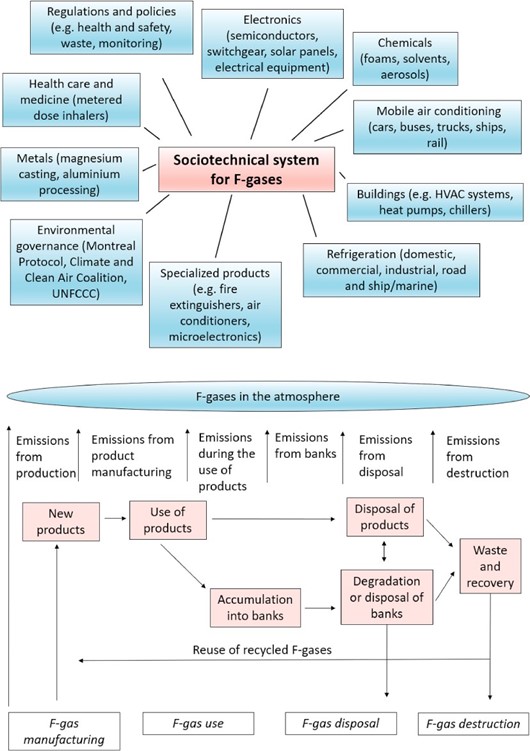

The uses of F-gases are replete within human society. Their applications are numerous ranging from industrial, commercial, domestic and medical uses. Modern civilization’s sociotechnical systems dependence on these synthetic and potent GHG’s represents potentially the most critical, yet poorly understood sociotechnical system related to CC (Sovacool et al.,2021). Image 5 illustrates the complexity of F-gas uses which are multi scalar and multi temporal in scope.

Image 5: F-gases as a sociotechnical framework (Source: Sovacool et al,2021)

Comprehensive studies of F-gas uses by humanity demonstrate no less than 21 categories of their emissions sources (Sovacool et al.2021; Harnisch, Stobbe & de Jager,2001). Appendix I provides a detailed breakdown of their numerous uses.

These include:

- Air Conditioning – Stationary, Mobile, and Buildings. Heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC)

- Refrigeration

- Materials – Plastics and Foams

- Fire fighting – Fire extinguishers

- Chemicals – Solvents and Aerosols

- Non ferrous metal production and processing – Magnesium and Aluminium

- Electronics – Semiconductors, LCD monitors and Screens, Circuit boards

- Electrical equipment and Switchgear

- Healthcare and medicine – Meter dosed inhalers

- Fumigation and pest control – Methyl bromide

- Double glazed and soundproof windows

- Use in Commercial products – Automobile tires, sports shoes, tennis balls, apparel

- Manufacture and use of renewable energy technologies – Solar panels, Wind turbines

- Leakage detection

- Atmospheric research and science

- Military applications

- By-product emissions of HCFC production

- Miscellaneous Industrial products

- Manufacturing and distribution losses

- Disposal, banks, recycling

- Destruction of F-gases

Image 6: Market shares of HFC consumption (Source: UNEP,2015)

The largest proportion of global usage of HFC’s is used for the refrigeration, air conditioning and heat pump sector (RACHP) at 86% of the GWP-weighted share of HFC consumption (Image 6) (UNEP,2015). This is in part why refrigerant management and the use of alternative refrigerants is hailed as the most impactful mitigation strategy against climate change (Hawken,2018).

Halogenated gases, the atmosphere and the terrestrial biosphere:

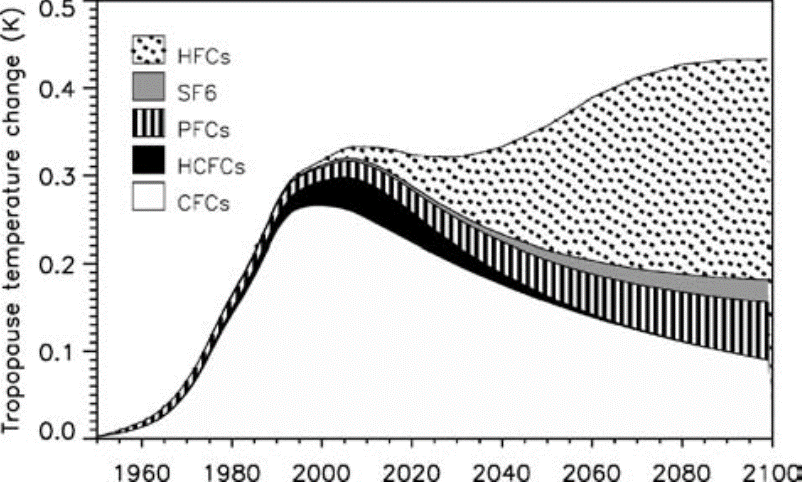

Current average global land temperatures are at around 1.2° C above the pre-industrial levels and are still rising (Hausfather,2020). The projected total emissions of halogenated gases alone could cause a temperature change of almost half a degree by 2100 (Forster & Joshi,2005) as shown in image 7. This temperature increase would come with effects on other processes such as increasing photorespiration and reducing photosynthesis of plants and increasing the feedback mechanism of increased H2O in the atmosphere via increased CO2 as well as increased temperature, which would cause yet more warming.

Image 7: The contribution of halogenated gas groups to the tropical cold-point temperature change since 1950 (Source: Forster & Joshi,2005)

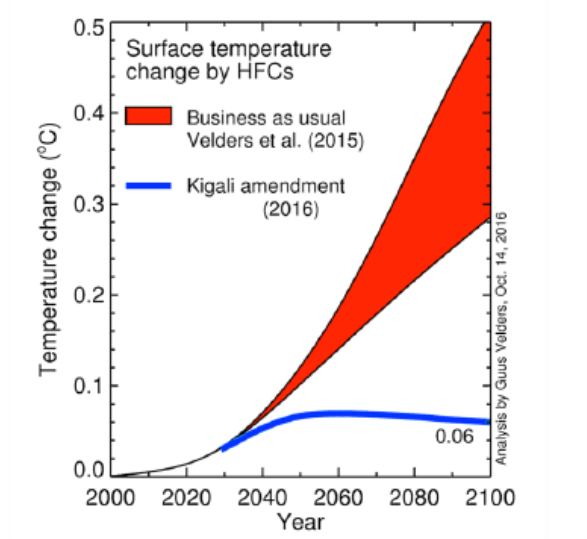

This warming could be mitigated fully by widespread adoption of the KA (IGSD,2018) (Image 8), which is yet to be ratified by all nations, with the notable abstinence of the United States of America (USA). This is subject to change with the announcement by the Biden administration that the USA will ratify the treaty within the first one hundred days of his office commencement (The Whitehouse,2021).

Image 8: Expected temperature changes with business-as-usual or the Kigali amendment protocols adhered to (Source: IGSD,2018)

Conclusions:

Halogenated gas emissions pose a significant risk as severe forcing agents for CC and their proper management is required to minimise the risk of their global warming impacts. These could include pushing terrestrial biomes beyond tipping points which would reduce and potentially eliminate the vital ecosystem services they provide as a powerful carbon sink. The multifarious uses of F-gases in our sociotechnical systems demonstrate how embedded our reliance on these chemicals are for the functioning of modern society. The Kigali amendment is the most recent effort to curb F-gas emissions but is yet to be ratified and implemented by all nations. It has the potential to mitigate up to 0.5°C of global temperature rise by 2100 through the phaseout and control of F-gases, predominantly HFCs. Such a temperature rise could threaten the delicate balance of our most powerful carbon sinks in rainforests with the notable example of the Amazon rainforest providing the greatest contribution to global land carbon strength capacity. With increasing temperatures from climate change reducing photosynthesis and increasing respiration rates due to effects on enzyme catalyzed reactions, it is ever more important to make global changes to our greenhouse gas emissions to prevent forest degradation and prevent the possibility of carbon sinks from transforming into net carbon sources. The effects of increased greenhouse gas emissions creating further temperature rise increases the global warming effect of water vapor in the atmosphere and also acts as a positive feedback loop. Other sources of human activities that reduce the land carbon strength capacity of rainforests come from the AFOLU sector where significant damage has been done and continues to be done to the ecosystem services which they provide. Deforestation for logging and animal agriculture are particularly the main causes for land use change and more needs to be done to protect these vital ecosystems.

This literature review could be expanded to discuss potential mitigation actions to limit warming that would occur from continued use of F-gases and the potential for strengthening and accelerating phaseout restrictions as well as discussing implementation of tighter controls over black-market trading of these controlled substances.

The implications of continued use of F-gases and their direct global warming potential will see continued global temperature rises and deleterious impacts on terrestrial carbon sinks such as the Amazon rainforest. This could offset progress of future actions taken to reduce global warming which poses an existential threat to humanity and biospheres globally. Research gaps that have been identified by a recent systematic literature review (Sovacool et al.,2021) include the identification of a need for crosscutting solutions and the need for more work on F-gases in developing nations such as China especially. An exploration of synergies between F-gases and other systems such as energy, transport and metal-working may be useful in identifying potential solutions.

The refrigeration, air conditioning and heat pump has been identified as the sector most responsible for the existing and future expanded uses of HFCs. If resources were available it would be worthwhile focusing on exploring methods to reduce the need for these activities such as green buildings which use physical methods to control internal air temperatures such as external shading and internal insulation methods.

References:

Congressional Research Service (2020) Hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs): EPA and State Actions. May 7 2020. Available at: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11541

Covey, K. Soper, F. Pangala, S. Bernardino, A. Pagiliaro, Z. Basso, L. Cassol, H. Fearnside, P. Navarette, D. Novoa, S. Sawakuchi, H. Lovejoy, T. Marengo, J. Peres, C.A. Baillie, J. Bernasconi, P. Camargo, J. Freitas, C. Hoffman, B. Nardoto, G.B. Nobre, I. Mayorga, J. Mesquita, R. Pavan, S. Pinto, F. Rocha, F. de Assis Mello, R. Thualt, A. Bahl, A.A. Elmore, A. (2021) Carbon and Beyond: The Biogeochemistry of Climate in a Rapidly Changing Amazon. Frontiers in Forests and Global Change, 4:618401 doi: 10.3389/ffgc.2021.618401

denman island climate action network (2021) How close are we to the temperature tipping point of the terrestrial biosphere? Available at: https://denmanislandclimateaction.ca/2021/03/24/how-close-are-we-to-the-temperature-tipping-point-of-the-terrestrial-biosphere/

Duffy, K.A. Schwalm, C.R. Arcus, V.L. Koch, G.W. Liand, L.L. Schipper, L.A. (2021) How close are we to the temperature tipping point of the terrestrial biosphere? Sci. Adv. Vol 7: eeay1052

Durkee, J. (2006) Chapter 2 – US and global environmental regulations, management of industrial cleaning technology and processes. Elsevier Science p 43-98 Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-008044888-6/50016-8

EIB (2016) ‘Short-Lived Climate Pollutants (SLCPs): An analysis of the EIB’s policies, procedures, impact of activities and options for scaling up mitigation efforts’The European Investment Bank November 2016Available at: https://www.eib.org/attachments/thematic/short_lived_climate_polluants_report_2016_en.pdf

EPA (2014) Greenhouse gas inventory guidance. Direct Fugitive emissions from refrigeration,air conditioning, fire suppression, and industrial gases. United States environmental protection agency November 2014 Available at:https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/140082/5555-fgases-factsheet.pdf

Forster, P.M. De F. Manoj, J. (2005)THE ROLE OF HALOCARBONS IN THE CLIMATE CHANGE

OF THE TROPOSPHERE AND STRATOSPHERE. Climatic Change, Vol 71: 249-266

Frank, D. Reichstein, M. Bahn, M. Thonicke, K. Frank, D. Mahecha, M.D. Smith, P. Van der Velde, M. Vicca, S. Babst, F. Beer, C. Buchmann, N. Canadell, J.G. Ciais, P. Cramer, W. Ibrom, A. Miglietta, F. Poulter, B. Rammig, A. Seneviratne, S.I. Walz, A. Wattenback, M. Zavala, M.A. Zscheischler, J. (2015) Effects of climate extremes on the terrestrial carbon cycle: concepts, processes and potential future impacts. Global Change Biology Vol 21. 2861-2880

Hausfather, Z. (2020) State of the climate: How the world warmed in 2019. Carbon Brief. Clear on Climate Available at: https://www.carbonbrief.org/state-of-the-climate-how-the-world-warmed-in-2019

Harnisch, J. Stobbe, O. de Jager, D. (2001) Abatement of Emissions of Other Greenhouse Gases “Engineered Chemicals”. IEA Greenhouse Gas R&D Programme. Available at: http://webcache.googleusercontent.com/search?q=cache:BQYF6CeL3rEJ:content.ccrasa.com/library_1/2634%2520-%2520Abatement%2520of%2520emissions%2520of%2520other%2520greenhouse%2520gases%2520%2523U2013%2520Engineered%2520Chemicals.pdf+&cd=1&hl=en&ct=clnk&gl=uk&client=firefox-b-d

Hawken, P. (2018) Drawdown The most comprehensive plan ever proposed to reverse global warming. Penguin Books, Great Britain 2018

Höglund-Isaksson, L. Purohit, P. Amann, M. Bertok, I. Rafaj, P. Schöpp, W. Borken-Kleefeld, J. (2017) Cost estimates of the Kigali Amendment to phase-down hydrofluorocarbons. Environmental Science and Policy, Vol 75: 138-147

IPCC 5AR WG1. (2013) Myhre, G., D. Shindell, F.-M. Bréon, W. Collins, J. Fuglestvedt, J. Huang, D. Koch, J.-F. Lamarque, D. Lee, B. Mendoza, T. Nakajima, A. Robock, G. Stephens, T. Takemura and H. Zhang, 2013: Anthropogenic and Natural Radiative Forcing. In: Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T.F., D. Qin, G.‐K. Plattner, M. Tignor, S.K. Allen, J. Boschung, A. Nauels, Y. Xia, V. Bex and P.M. Midgley (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA .Page 666

IGSD, Institute for governance and sustainable development (2018) Primer on HFCs: Fast action under the Montreal Protocol can limit growth of hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs), prevent 100 to 200 billion tonnes of CO2-eq by 2050, and avoid up to 0.5°C of warming by 2100. IGSD working paper: 11 January 2018 Available at: http://www.igsd.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/HFC-Primer-v11Jan18.pdf#:~:text=Primer%20on%20HFCs%20Fast%20action%20under%20the%20Montreal,avoid%20up%20to%200.5%C2%B0C%20of%20warming%20by%202100

Lenton, T.M. Rockstrom, J. Gaffney, O. Rahmstorf, S. Richardson, K. Steffen, W. Schellnuber, J. (2019) Cimate tipping points – too risky to bet against. Nature Vol. 575 Comment pp. 592-595

Liang, L.L. Arcus, V.L. Heskel, M.A. O’Sullivan, O.S. Weerasinghe, L.K. Creek, D. Egerton, J.J.G. Tjoelker, M.G. Atkin, O.K. Schipper, L.A. (2018) Macromolecular rate theory (MMRT) provides a thermodynamics rationale to underpin the convergent temperature response in plant leaf respiration. Glob. Change. Biol. Vol 24: 1538-1547

Ma, S. Osuna, J.L. Verfaille, J. Baldocchi, D.D. (2017) Photosynthetic responses to temperature across leaf-canopy-ecosystem scales: a 15-year study in a California oak-grass savanna. Photosynth Res. Vol 132: 277 -291

Marcucci, A. Kypreos, S. Panos, E. (2017) The road to achieving the long-term Paris targets: energy transition and the role of direct air capture. Climate Change Vol. 144 p.181-193

Nobre, C.A. Sampaio, G. Borma, L.S. Castilla-Rubio, J.C. Silva, J.S. Cardoso, M. (2016) Land-yse and climate change risks in the Amazon and the need of a novel sustainable development paradigm. PNAS Vol. 113 no. 39 10759-10768

Norman, C.S. DeCanio, S.J. Fan, L. (2008) The Montreal Protocol at 20:Ongoing opportunities for integration with climate protection. Global Environmental Change Part A: Human & Policy Dimensions Vol. 18(2) p.330-341

Qin, Y. Xiao, X. Wigneron, J-P, Ciais, P. Brandt, M. Fan, L. Li, X. Crowell, S. Wu, X. Doughty, R. Zhang, Y. Liu, G. Sitch, S. Moore III, B. (2021) Carbon loss from forest degradation exceeds that from deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon. Nature Climate Change, Vol 11: 442-448

Roberts, M.W. (2017) Finishing the job: The Montreal Protocol moves to phase down hydrofluorocarbons Review of European, comparative & international environmental law, Vol.26 (3), p.220-230

Roman-Cuesta. R.M. Rufino, M.C. Herold, M. Butterbach-Bahl, K. Rosenstock, T.S. Herrero, M. Ogle, S. Li, C. Poulter, B. Verchot, L. Martius, C. Stuiver, J. de Bruin, S. (2016) Hotpots of gross emissions form the land use sector: patterns, uncertainties, and leading emission sources for the period 2000-2005 in the tropics. Biogeosciences Vol. 13 4253-4269

Shah, N.Wei, M. Letschert, V.E. Phadke, A.A. (2015) Benefits of Leapfrogging to Superefficiency and Low Global Warming Potential Refrigerants in Room Air Conditioning. Lawrence Berkely National Laboratory. LB Report number: LBNL-1003671 Available at: https://eta.lbl.gov/publications/benefits-leapfrogging-superefficiency

Sovacool, B.K. Griffiths, S. Kim, J.Bazilian, M. (2021) Climate change and industrial F-gases: A critical and systematic review of developments, sociotechnical systems and policy options for reducing synthetic greenhouse gas emissions. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews, 141: 110759

The Whitehouse (2021) Executive order on tackling the climate crisis https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/presidential-actions/2021/01/27/executive-order-on-tackling-the-climate-crisis-at-home-and-abroad/

UNEP (2019) Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol on Substances that Deplete the Ozone Layer – Decision XXVIII/1: Further Amendment of the Montreal Protocol Available at: https://ozone.unep.org/sites/default/files/2019-04/Original_depositary_notification_english_version_with_corrections.pdf

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) (2015) Fact sheets on HFCs and Low GWP Alternatives. Fact Sheet 2, Overview of HFC Market Sectors. Available at: https://ozone.unep.org/sites/ozone/files/Meeting_Documents/HFCs/FS_2_Overview_of_HFC_Markets_Oct_2015.pdf

WMO (2014) (World Meteorological Organization), Assessment for Decision-Makers: Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion: 2014, 88 pp., Global Ozone Research and Monitoring Project—Report No. 56, Geneva, Switzerland

Appendix I: Halogenated gases by usage category, specific uses and application types. (Source: adapted from Sovacool et al.,2021, Harnisch, Stobbe & de Jager,2001)

| Halogenated gas emissions source category | Subcategories and specific uses of halogenated gases | Halogenated gas Classes and applications in uses |

| Air Conditioning | Stationary – Space cooling Buildings – Heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) – Direct and reversible heat pumps Centralised systems Secondary chillers – eg. Basement operated and distributed cooling Mobile – Cars, trucks, busses, railroad, aircraft | HFCs & PFCs +(Refrigerants) |

| Refrigeration | Domestic Small commercial Supermarket Cold storage and food processing Industrial Refrigerated transport – reefer ships, containers, railcars, road – transport refrigerated units (TRU’s) | HFCs & PFCs +(Refrigerants) |

| Materials | Plastics and Foams: Polyurethane – Rigid: Automotive parts, Insulation (including for refrigerators and freezers), Varnish. Flexible: Tubing – pipes and hoses Integral skin: Shoe soles, Furniture cushions and padding Extruded polystyrene – Underlay, insulation, packaging Polyolefins: Polypropylene – packaging, plastic bags Polyethylene – foam mats Polyisocyanurate – insulation Phenolic foams – insulation (fire resistant) | HFCs +(blowing agents) |

| Firefighting | Fixed flooding systems – sensitive systems like computer and telecommunications servers, military and security applications Portable | HCFCs, HFCs, PFCs +(Agent) |

| Chemicals | Solvents – Metal-working, optical, precision engineering, aerospace, medical technology industries: Degreasing, Cleaning agents (metals, glass, gemstones) Aerosols – household: Compressed air and spray servicing – tire inflaters, freezer sprays, animal repellants, cosmetic aeorosols (hairspray, deodorants), food dispensing products, spray paint, novelty aerosols (artificial snow, plastic string, noise makers), household cleaning sprays, room fresheners, spray adhesives Technical: de-dusters eg. For photographic negatives, aircraft insecticides | HFCs +(propellant) HFCs +(Agent) |

| Non-ferrous metal production and processing | Primary aluminium production – smelting and processing Magnesium casting – smelting, processing of ingots and recycling | PFCs +(processing) SF6 +(secondary casting) NF3 +(cover gas) |

| SF6 & NF3 +(cover gas) | ||

| Electronics | Semiconductor manufacturing – Process management, prepare surfaces for deposition of copper film (metallization), clean and remove contaminants (desmearing), exhaust gas cleaning, chamber cleaning (cleaning chemical vapor deposition (CVD) chambers, Plasma etching, Printed circuitboard manufacturing LCD monitors and screens – Flatscreen televisions, Monitors and screens: GPS navigation screens, handheld videogames | HFCs +(cleaning agent)+(etching gas) PFCs +(etching gas) SF6 +(chamber cleaning) NF3 +(chamber cleaning) |

| HFCs & PFCs+(etching gas) SF6 & NF3 +(chamber cleaning) | ||

| Electrical equipment and switchgear | Manufacture and testing of gas insulated switchgear (GIS), leakage from maintenance, operation and malfunction of GIS, Bushings, gas-insulated lines, high voltage and vacuum circuit breakers, ring main units, high voltage outdoor instrument transformers | SF6 +(arc quenching and insulation gas) |

| Healthcare and Medicine | Metered dose inhalers (MDI) Volatile inhalation anaesthetics Retinal detachment surgery Contrast-enhanced ultrasound | HFCs+(propellant) |

| CFCs (haloethane, enflurane, isoflurane)+(agents) HCFCs (sevoflurane, desflurane)+(agents) SF6+(tamponade) | ||

| SF6+(agent) | ||

| Fumigation and pest control | Agricultural fumigation – biocide for soils Treatment of wood, structures and durable commodities – eliminate pests and rodents Disinfecting of perishable goods – preserve for transport, avoid transfer of pests for exports/imports | Methyl Bromide +(agent) Sulfuryl Fluoride +(agent) |

| Double glazed and soundproof windows | Sound abatement | SF6 +(filling gas) |

| Use in commercial products | Automobile tires, sports shoes, tennis balls, apparel | SF6 +(filling gas) PFCs & SF6+(shock absorbing gas) |

| Manufacture and use of renewable technologies | Thin film solar modules | HFCs, PFCs, SF6 +(etching gas) NF3+(chamber cleaning) |

| Wind turbines switchgear (GIS) | SF6 +(arc quenching and insulation gas) | |

| Leakage detection | Air exchange measurements in architecture or building design Testing piping systems, test integrity of vacuum apparatus Precision localization of leaks in water-bearing pipes of district heating systems | SF6+(tracer gas) |

| Atmospheric research and science | Air current and GHG diffusion measurements Chemical tracer to detect cold air currents Environmental meteorology – air movements, distribution of odours or vapours in low wind situations Atmospheric measurement of methane emission by cattle Measuring impact of nuclear weapon explosions X-ray material testing X-ray linear accelerator for medical therapy Electron microscopes | SF6+(tracer gas) |

| Military applications | Refrigeration in nuclear submarines and other confined spaces Wind supersonic channels Insulation of airborne warning and control system (AWACS) radar domes | HFCs+(refrigerant) SF6+(Sound abatement) SF6+(AWACS radar insulation) SF6+(wind supersonic channels) |

| By-product of HCFC-22 production | HFC23 by-product of HCFC-22 production | HFC23 +(by-product) |

| Miscellaneous industrial products | Production of polymers, solvents, pharmaceuticals (Ibuprofen), paper production, heavy duty anti corrosive and adhesive, motorway parking paint, automotive belts and hoses, gaskets, rafts and rescue boats, armour, helmets, containers for dangerous good, protective clothing, generation of high-grade graphite for graphitisation | Miscellaneous |

| Manufacturing and distribution losses | Diffusive losses during manufacture and packaging | ALL+(diffusive losses) |

| Disposal, Banks and Recycling | Diffusive losses | ALL+(diffusive losses) |

| Destruction | Diffusive losses | ALL+(diffusive losses) |